| Arete Quarterly Q413.pdf |

The new year often harkens a time of hope and new beginnings. Sometimes it's just nice to have a tough year behind us and sometimes there are new tangible opportunities to savor. Either way, wouldn't it be nice if you didn’t have to just wait and see how things turned out? Wouldn’t it be nice if you could script your own story?

In an important sense, you can do exactly this. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller, by John Truby, provides a fun and accessible roadmap to create your own page turner. In the context of investing, which tends to get very serious very quickly, storytelling provides a useful, but more light-hearted exercise.

For example, what if you were the main character in a story in which you faced down investment challenges and adversity? It's hard going at first, and you have setbacks, but ultimately you rise above the challenges and succeed in your quest!

As Truby states upfront, "Stories are really giving the audience a form of knowledge— emotional knowledge— or what used to be known as wisdom, but they do it in a playful, entertaining way." The key point is that, "All stories are a form of communication that expresses the dramatic code," which in turn, “is an artistic description of how a person can grow or evolve." In short, stories are tales about growing and evolving.

Truby goes on to to describe that, “The focal point is the moment of change, the impact, when a person breaks free of habits and weaknesses and ghosts from his past and transforms to a richer and fuller self … And that’s why people love it [storytelling]."

So as you are drafting your own investment story, what "habits and weaknesses and ghosts from the past" does your hero struggle with? How does the character transform into a “richer fuller self?”

I know I’ve personally had many revelations through my career as an analyst and portfolio manager and one early “weakness” was simply learning to respect the knowledge I had developed. I had always thought that the big investment firms somehow had a higher level of understanding than I did. If something they did struck me as odd or misguided, I first assumed I must be missing something.

After I paid down my student loans and began to invest more seriously, I enjoyed a fair amount of investment success and realized I wasn’t missing anything. I increasingly realized that asset growth drove decisions at a lot of firms in ways that eroded the value that investors received. Even as a portfolio manager, many important factors were completely outside of my control.

So, coming back to your story, what issues does your hero struggle with? Does s/he get overwhelmed by day-to-day activities that squeeze out time to work on investing? Does the hero get stuck in the weeds of details and miss some really important issues? Does he or she never quite feel comfortable about where the pitfalls are and how to avoid them? How will your hero overcome those obstacles and transform into a “richer fuller self?”

While I always hope things turn out well for people on a personal level, from a business standpoint, I am deeply ambivalent about the outcomes. On one hand, Arete’s hallmarks of valuation and long investment horizon benefit disproportionately when swarms of market participants chase fads, obsess over short-term trading, and accept risk indiscriminately. We make money by being on the other side of those decisions and appreciate the opportunities they afford us.

On the other hand, we also believe strongly that large swaths of investors who aren’t inclined to such frivolity, still aren’t getting nearly as much value from their money managers as they deserve. For these investors, Arete can be a valuable resource in exploring possibilities for their heros.

In sum, the importance and seriousness of the investment process paradoxically often inhibits a constructive discussion of it. In these cases, storytelling may serve as a useful antidote to re-frame and reconsider important issues. If you’re interested in writing or re-writing your investment story, please consider Arete in helping your hero to overcome obstacles!

When people ask me, "How's business?" there are always so many things going on, that it's often hard to summarize in any meaningful way. One thing I can say with certainty is that the tools available for information gathering, analyzing, and learning keep getting better and cheaper. These advances vastly improve the process of building knowledge and are a big part of what makes my job so fun!

Indeed, knowledge building is one of the areas for which I am truly optimistic, and not just for Arete. Technology writer and author, George Gilder, contrasted manufacturing of physical items with that of knowledge: "Material is conserved, as physics declares. Only knowledge accumulates. All economic wealth and progress is based on the expansion of knowledge."

This phenomenon is important to Arete’s business for a variety of reasons. For one, due to my own personal interests and intellectual curiosity, Arete is particularly adept at learning and building knowledge. The company’s independent ownership also substantially facilitates this activity by strongly incentivizing interpretations of information that are well anchored to economic reality and investors’ needs. As a result, the business is establishing yet another dimension of competitive advantage.

Knowledge building is valuable for more than just internal purposes, however; it also helps Arete connect with, inform, and serve investors. This is so because the distribution of knowledge is deeply uneven across the marketplace of investment service providers. Very few are constructed so as to gather, process, analyze, and synthesize information into a base of knowledge that can cut through the noise. At any level of investing, this is extremely important.

One striking testament to the disparity in knowledge capabilities was revealed by John Minahan, former Director of Research for NEPC, one of the largest and most reputable pension consulting firms. In a presentation in February 2011, Minahan told the Baltimore CFA Society that he essentially learned the investment business from the managers he was responsible for evaluating. According to Minahan, the resources at money management firms tend to be so much greater and therefore they are often privy to much greater insights.

This arrangement often leaves individual and small- to mid-sized institutional investors in a bind. For most investors, their primary contact is an advisor, consultant, or relationship manager, not the person or people directly involved in the investment process. While some of these representatives are outstanding and extremely well-informed, many are not. The frustration from just such a situation in a recent meeting was expressed by way of the rhetorical question, “Do you ever really talk to the person managing the money?” The vast majority of the time you don’t.

As a result, one of the ideas I’m exploring is to see if there are ways Arete can help bridge this important gap between the types of insight investors need, both individually and as fiduciaries serving on behalf of others, and what they are currently (often not) receiving from their primary relationships. One key area where I fear many mistakes are being made is in determining expected returns -- which directly affects asset allocation decisions. Some things may be as simple (but important!) as establishing an appropriate investment policy. It is hard being a chief investment officer in the best of times; it is much harder when you just don’t have the resources.

One goal I have with this effort is simply to get in front of more investors this year to talk about how Arete does things and to explore ways in which to better leverage its knowledge base. While stocks and valuation remain core strengths, my Kellogg degree and CFA training, along with experience approaching twenty-five years now, give me a broad set of skills from which to help investors analyze, evaluate, and hopefully improve their situation. If you know of a person or an organization that might be interested in exploring ideas to work together, I’d really appreciate hearing about them.

Finally, in the Ideas section of Arete’s website, I point out that, “The culture of Arete is built around ideas. One way in which we try to differentiate ourselves is to apply fresh thinking to everything we do.” This statement highlights the reality that ideas and knowledge management are core to the fabric of Arete and have been from the very beginning. As a result of this orientation, it is rare that I don’t have some insights that can be helpful and I always have fun tossing ideas around. If you have any interest in brainstorming some possibilities with me, please let me know. I’d love to grab lunch or a cup of coffee and see if there is anything Arete can do!

Thanks and take care!

David Robertson, CFA

CEO, Portfolio Manager

It seems silly, but the market is still following the Fed’s lead like a little puppy obediently following its master. Despite the continued strength in the fourth quarter, however, we did notice a hint of a change in character of the market. This change was driven primarily by the consideration of, and eventual acknowledgement of, a reduction (tapering) of the quantitative easing program and revealed reactions similar to what we saw at the end of the second quarter when tapering first became a headline topic.

Even though the initial tapering is very modest, it likely signals an end to the era of easy directional bets. The bets have been made on the (we would argue flawed) logic that the market will go up in proportion to the amount of money being injected by the Fed. They also represent a belief that the Fed is in control. Since these bets are occurring during a period of record high margin debt and ever-increasing disconnection from economic fundamentals, the risk of big changes to the market dynamics from relatively small changes in uncertainty is quite high.

The evidence of large directional bets is substantial and varied. Certainly the flow of funds out of active mutual funds and into passive funds -- index funds and ETFs, is one key indicator. We also see the passive flows affecting individual stocks as the valuations of major index components are pulling away from those of stocks not in major indexes.

Unfortunately for investors, the market cap structure of most major indexes systematically exacerbates valuation errors, increasing their exposure to wild swings. Since overvalued stocks get overweighted in such indexes, and undervalued stocks get underweighted, new flows to index funds exacerbate market swings by stretching valuations on both ends of the spectrum.

Interestingly, the relative performance of Arete’s mid cap core (AMCC) strategy tends to be a mirror image of the Fed-induced levitation. Since well over 90% of AMCC’s holdings by weight are different from the index, it tends to have significant exposure to the undervalued and underweighted index components and therefore can behave very differently. Recent improvements in AMCC’s relative performance also provides some indication that the era of directional bets may be peaking.

Insofar as this is the case, AMCC is positioned to benefit from two separate tailwinds. First, the strategy’s large cash position will serve as a major buffer to market declines and also provide dry powder to invest in stocks that get oversold. Second, AMCC’s holdings should be much more resilient as the market begins to discount an impending increase in cost of capital.

While these observations provide a useful encapsulation of the market action in the fourth quarter, it is still critically important to keep the big picture in mind. Despite an almost constant onslaught of distractions, the key issue has been, and continues to be, DEBT.

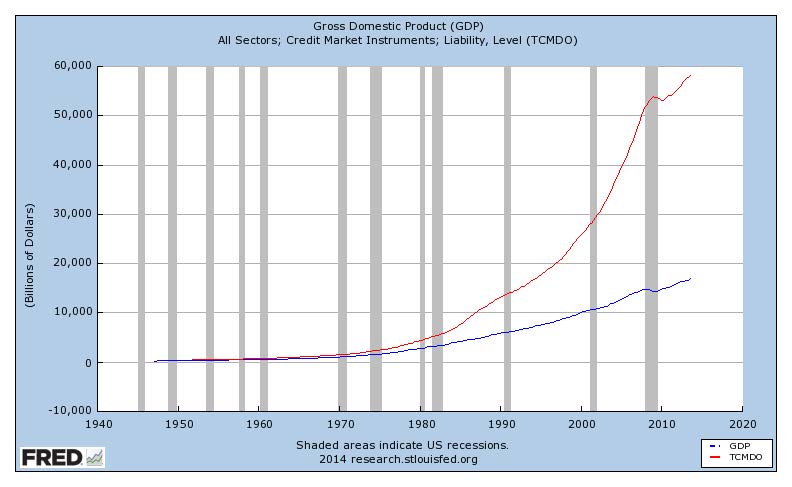

The graph below captures beautifully the increasing trajectory of total debt (red line) to GDP (blue line). No individual can maintain this path forever nor can any nation. The unsustainable path of debt relative to GDP constitutes a system from which all other financial phenomena emanate. Everything you read and hear about investing is affected by whether the source comes from within the system or remains outside of it.

It’s important to understand systems because when strong ones are in place, they significantly constrain and/or overwhelm the impact of individual actions. Interestingly, none other than management guru, Peter Drucker, articulated the prominent role of systems when he discussed organizational design.

In the 2009 Harvard Business Review article, “What would Peter Say?”, Rosabeth Moss Kanter wrote, “He [Drucker] took a broad look at the context surrounding organizations, noting jarring events he called discontinuities. Next, since the signs of difficulties ahead were there all along, he might follow up by telling us, ‘Look at the underlying systems.’ Drucker rarely named or blamed individuals; he saw root causes in the design of organizations – in their structures, processes, norms, and routines.”

Drucker’s analysis provides a useful analog from which to think about the system of the debt-driven economy and capital markets we have. First, when “discontinuities” occur, often the signs have been there all along. Just as the conditions of extended credit were around for decades before the financial crisis in 2008, it is important to realize that the fragility caused by those conditions has not gone away. The signs are still here.

Second, while there was plenty of blame to go around, the primary causes of the crisis in 2008 were not individual actions; the root causes were in the design of an economy and financial system that was completely dependent on continued credit expansion. This led to a “bigger is better” mentality throughout the economic ecosystem even though that design was not sustainable.

The effects of ever-expanding credit and “bigger is better” thinking have extended far and wide and have been especially pronounced in the investment business. It’s important for investors to understand that a huge proportion of the investment services industry is also part of this same system, built on cheap credit and focused on growth, and therefore subject to the same risks.

Some consequences of this dynamic were captured well by Seth Klarman in his March 2, 2011 letter entitled, “Our National Predicament.” In it, he described that, "Most investors feel compelled to be fully invested at all times -- principally because evaluation of their performance is both frequent and relative. For them, it is almost as if investing were merely a game and no client's hardearned money was at risk. To require full investment all the time is to remove an important tool from investor's toolkits: the ability to wait patiently for compelling opportunities that may arise in the future." The current vernacular in the market is FOMO -– “Fear of Missing Out.”

One of the reasons Drucker’s perspective is so useful is because it reconciles the inadequate investment results that inevitably result from a flawed system with the positive feelings most people have about their advisor(s)/manager(s). While it is absolutely fair to say that there are a lot of smart and well-intentioned people in the business, it is not fair to say that client portfolios benefit from all of their best insights -– that’s not how the “system” works.

I’ve had plenty of my own run-ins with the “system” and it’s been eye-opening. At one firm, we started receiving calls from headquarters every day shortly after the market closed at 4:00 demanding an explanation for the portfolio’s relative performance. Needless to say, this effort placed a great deal of pressure to manage to a time horizon much shorter than what most investors expected.

In addition, I was a technology analyst in the late 1990s during the internet boom. At the time I clearly saw valuations extending way, way beyond reasonable levels and read dozens of IPO prospectuses that conveyed no viable business models. Despite daily efforts to reduce and manage the technology exposure, I lost the battle. Unfortunately, as a result, investors in the funds also lost a lot of money. It turns out there was an intractable commitment to maintain market sector weights despite overwhelming analytical evidence to the contrary. This is a good example of how the “system” works.

Lest you think the credit “system” is an outlandish narrative, it actually represents a well-known moral argument upon which many stories are based. Black Comedy is, “The comedy of the logic – or more exactly, the illogic -– of a system,” as defined by John Truby in The Anatomy of Story (mentioned in the “Welcome” article). He continues, “This … form of storytelling is designed to show that destruction is the result not so much of individual choice but of individuals caught in a system that is innately destructive.” Dr. Strangelove is a well-known example of this type of moral argument.

The insight from Black Comedy is hugely important: If you are “caught in a system that is innately destructive,” the result has virtually nothing to do with individual choice. The lesson that derives from it is: If you are in such a system, either hope your assessment is wrong, or make sure to distance yourself from it.

As it pertains to the markets, this leaves investors with two very distinct general courses of action. If you don’t believe the unsustainable debt thesis, by all means, increase your exposure to risk assets at any signs of credit extension or liquidity provision. If you do believe the unsustainable debt thesis, as Arete does, then you need to operate outside of that system to the greatest possible extent. In particular this means finding managers who don’t “feel compelled to be fully invested at all times,” who can “wait patiently for compelling opportunities to arise in the future,” and who don’t get caught up in the “bigger is better” race.

Indeed, the degree to which any investment firm operates outside of the “system” may be one of the best and most important differentiators available. Remember though that this won’t be advertised; almost all industry participants are going to say the same things. The task is to figure out what firms are actually doing. The reward for successfully distinguishing will help keep you out of a system from which you have little control.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed