January 2015

The Financial Times recently described 2014 as "a biblically bad year for active management." While the market had another strong year, the majority of actively managed funds trailed behind. The characteristics that made it so difficult for active managers were readily apparent in the fourth quarter.

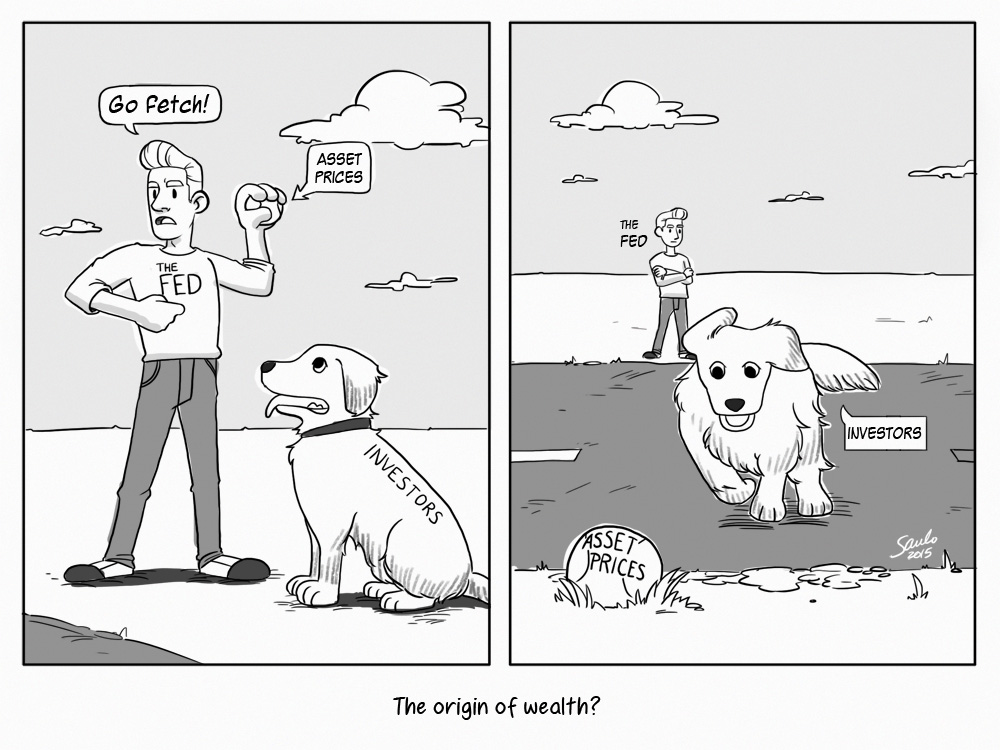

Early in the quarter the market suffered a significant correction which seemed like It might be a long-awaited emergence of risk aversion in light of extended valuations, credible risks, and deteriorating market action. In yet another replay of the Fed's playbook from the last five years, however, several Fed members immediately issued statements to alleviate concerns and the market dutifully obeyed by fully retracing the losses and setting new highs. Easy.

Well, it’s easy if you’re a Golden Retriever chasing a ball. Not so much if you’re an active manager who is trained to analyze business and economic fundamentals and to act in your client’s best long-term interests. Indeed, the Fed's policy to encourage risk-taking has crossed some important signals for active managers. This has presented them with an untenable dilemma: Stick to your guns of managing to economic fundamentals and risk being trumped by the Fed whenever things slow down, or, follow the Fed's cue knowing full well it probably won't end well, but living to fight another day. While this policy direction of the Fed has made life hard on active managers, it has also done something else of note: It has made the economy and the market dumber.

This isn't schoolground name-calling either. In one of the most influential books to our thinking, The Origin of Wealth, author Eric Beinhocker’s main thesis is that the origin of wealth is knowledge. In explaining this, he provides us with a very useful framework from which to judge the condition of the economy and the markets.

Beinhocker goes on to specify that the origin of wealth isn’t just any knowledge, but knowledge that is fit for purpose. In addition, since evolution is essentially a powerful learning algorithm, it serves as a terrific guide for arriving at knowledge that is fit for purpose. In fact, the three general phases of evolution, experimentation, selection, and amplification can be applied to the economy as a whole to provide some interesting insights.

The experimentation stage corresponds fairly intuitively with entrepreneurship which can be measured in a number of ways. The bad news is that the popular headlines of successful IPOs and the widely held belief in this country's entrepreneurial vigor belie a more unpleasant reality.

Economist Gary Shilling, for example, noted in his December newsletter that, "New business formations have been falling steadily since the 1990s, and intensifying since the Great Recession." Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan found the same evidence in a 2014 Brookings Institute report on entrepreneurship. The authors report that, “Recent research shows that dynamism is slowing down. Business churning and new firm formations have been on a persistent decline during the last few decades, and the pace of net job creation has been subdued. This decline has been documented across a broad range of sectors in the U.S. economy, even in high-tech.”

The trends have been so prominent as to prompt Shilling to ask, "Where are all the entrepreneurs?" and prompts us to ask, "Why isn't this critical development receiving a lot more attention?"

Two important points come out of the analysis of business dynamism. One is that the number of jobs created by new establishments has declined materially since a peak in the late 1990s. Since jobs created by new establishments are significant contributors to overall job growth, this trend suggests that sustainable job growth will likely be lower than what we have enjoyed over the past fifteen years or so. The second point is that fewer new businesses implies less "experimentation" and therefore a diminished capacity by the economy to seek out interesting new growth opportunities.

The selection and amplification phases of evolution are also fairly easy to apply since they correspond to the flow of resources. Since capital is often the scarcest resource, capital market flows point us towards the types of businesses that are most fit for purpose in a particular environment, and therefore, should be amplified.

In a world of very low (and artificially suppressed) interest rates, the answer tends to be large, public, incumbent firms. This happens because they have a competitively advantaged cost of capital; it is almost free for them. Competitors not only have to pay more, but often cannot access appropriate capital at all. Further, "Big companies are fundamentally geared toward exploiting their legacy businesses and strategies; this is what they focus their talent and resources on and what they measure." As a result, low rate policy tends to subsidize the status quo by encouraging resources to flow away from the economic elements most likely to seek change.

Judging by the merits of the evolutionary model, then, Fed policy is actually making things worse, not better. Not only has such policy coincided with a substantial decline in entrepreneurial dynamism which limits the economy's ability to "learn", but it also actively redirects resources away from such "learning" ventures to the benefit of incumbent firms which are inherently biased against change.

It is especially tragic that this policy stance is so interventionistic because evolutionary systems have their own natural balancing and rebalancing mechanisms. Beinhocker writes: "Interestingly, [John] Holland has shown that evolution automatically strikes the right balance between exploration and exploitation. When things are good, when evolution has found a high plateau, evolution will devote proportionally more population resources to exploiting. But when things are bad, when the population is down in the valley, proportionally more resources will be devoted to exploring. Every time evolution occupies a new part of the fitness landscape, it is placing bets to sample the unknown. But like any bettor, as evolution gets more information, it wants to double up on the bets that look most promising."

In fact, the evolutionary process proves most powerful during periods of transition. As Beinhocker points out, "Markets win over command and control, not because of their efficiency at resource allocation in equilibrium, but because of their effectiveness at innovation in disequilibrium." Given the headwinds of high and rising levels of debt, weakening demographics, soon-to-be exploding health care costs, rising income inequality, and underutilized resources, among other challenges, it is hard to argue that we are anywhere close to a comfortable equilibrium. Wouldn't it be nice to be able to fire up some extra innovation at times like this to help plough through the challenges?

Interestingly, rather than operating under a philosophy that the origin of wealth is knowledge, the Fed seems to be operating under a modified view that the origin of wealth is "narrative". Until this changes, the economy is likely to remain handicapped in its efforts to recover and investors will be left to contending with the same untenable dilemma. This is deeply unfortunate for a wide variety of reasons, but there are reasons to be optimistic.

For one, the longer Fed policies demonstrably fail, the harder they will be to maintain. In the meantime, despite such misguided efforts, there are still plenty of great things happening within the economy. Lots of terrific (and cheap!) technology, business tools, and education are widely available and are being combined to automate systems, discover new health care solutions, and make a lot of things better. This process will continue and has the potential to accelerate if the brakes of public policy are ever released. It could accelerate quite significantly if public policy actually becomes constructive. If all of this happens after asset prices fall to much lower levels and you have cash, it could be a once in a lifetime opportunity.

Finally, for those unconvinced of the "knowledge" theory of wealth, and for those who are more inclined to invest on the basis of whether the word "patient" in the Fed's minutes means more or less than six months than by analyzing economic fundamentals, we have a few words.

To be sure, exceptionally strong market returns for the last six years can be interpreted as the market's acceptance of the efficacy of low rates. Such an interpretation could also reference the "wisdom of crowds" as the arbiter of what is working and what isn’t. While there is no doubt that the market has been strong and that consumer and adviser sentiment is extremely high, there is also no doubt that crowds do not always create wisdom.

While this is absolutely not a new insight, it bears some consideration as the "wisdom of crowds" meme has swept our culture. This very issue was addressed by John Kay in a recent Financial Times piece with Kay noting, "The wisdom of the crowds has become a modern cliche. And a strange one -- the crowds that attended the Nuremberg Rallies, or cheered the tumbrils of the Reign of Terror, were anything but wise." He goes on, "How could large numbers of people, so similar to ourselves, behave like that? What on earth were they thinking?"

According to Kay, "The answer to the question, 'what were they thinking?' is that, mostly, they were not thinking at all. That is often the nature of social behavior." And this is an absolutely key point. While under certain conditions, crowds can produce insights not available to any individual, it is also true that crowds can produce social behavior that increases herding and minimizes thinking. Kay continues: "The wisdom of the crowds becomes a pathology when the estimates of the members of the crowd cease to be independent of each other, and this is likely when the crowd is large, ill-informed, or both. It is the nature of a crowd to turn on anyone who dissents from what is already average opinion." The result is a form of enforced complacency -- which also happens to strongly resemble current sentiment.

What does all of this mean? If there is one lesson to take home from this discussion it is that knowledge serves as an excellent standard by which to judge real wealth creation. At a time when many investors have become so conditioned to following every nuance of the Fed's narrative, it is nice to have a beacon to help keep us on the right track. This is especially helpful when the Fed's policy of low rates and ongoing narrative have served not as a welcome bridge over a rough patch, but rather as a detour that is taking us further and further away from our desired destination of sustainable economic progress.

With public asset prices dangerously decoupled from economic fundamentals it is more accurate to say that current prices represent wealth illusion more than real wealth. Certainly this uneasy condition could persist for some time longer, but the ultimate reckoning will be the same. Whether the Fed voluntarily allows rates to normalize, or some external event or events cause rates and risk aversion to rise, or reported results simply become far too unimpressive to substantiate such considerable investor support, the outcome will be similar. Everyone who has remained invested until sentiment changes is going to be involved in a very competitive race to the exits that will seriously challenge their ability to convert illusory wealth into permanent wealth. All of which is to say that maintaining exposure here represents speculative activity much more closely than it represents true investing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed