The stock market's roller coaster ride this year is beginning to cause a certain amount of apprehension among investors. What has prompted the recent weakness? Is the recent decline just another bump in the road or the beginning of a prolonged downturn? Should adjustments be made to the portfolio?

Most financial analysis focuses on factors such as cash flows, growth expectations, and balance sheet strength, and rightly so. The relevance of these factors to asset prices is strongly supported by both theoretical and empirical evidence. Yet one of the most basic tenets of economics is that price is a function of supply and demand. While investors tend to hear a lot less about the supply and demand for stocks themselves, this relationship can also have a meaningful influence on prices.

In order to fully understand the supply/demand dynamics for stocks, it is important first to remember the difference between primary and secondary markets. In primary markets, a good is manufactured or provided and a price is established by the provider. Those providers make their best estimates as to what the prices should be. In secondary markets, a pre-existing good is traded. Price is determined by the interaction of buyers and sellers as the point at which supply equals demand.

A common misperception is that stocks are priced like primary goods (which is only true of initial public offerings). There is a price for the product, you decide to buy or sell it, and that's that. You either have the stock or you don't. Such thinking is often enabled, if not encouraged, by the financial media. For example, the Financial Times reported [here] (in regards to bonds, though it is just as relevant for stocks), "Investors have pulled almost $6bn out of corporate bond funds in the past week, in the latest sign of nervousness about companies' debt pile in an environment of rising US interest rates and falling oil prices."

Financial securities like stocks and bonds, however, are normally priced in secondary markets. This means that when a stock is bought or sold, it is really exchanged between the buyer and seller. The price is established by determining the price that clears the market, i.e., balances the demand from buyers with the supply from sellers. As John Hussman instructs [here], "[O]nce a security is issued, whether it’s a government bond or a dollar of base money [or a share of stock], that security must be held by someone, at every point in time, until that security is retired."

Therefore, while the statement about bond funds is true, it is also true that "investors have added $6bn into corporate bonds in the past week". Why? Because when owners of mutual bond funds sell shares, the mutual fund company generally needs to sell bond holdings, and when they do, some other investors need to buy those bonds. As a result, the story reveals very little about whether corporate bonds should be bought, held, or sold. It only reveals the behavior of investors in corporate bond mutual funds, which is only one subset of the universe of all of investors.

What the story does reveal, at least indirectly, is that different investors have different goals, different investment horizons, and different levels of risk tolerance. These can all change over time and affect demand.

The demand for existing homes provides a useful example. Such demand is not level through the year; a disproportionate number of prospective home buyers appear in the spring and summer months. As a result of this imbalance, home sellers tend to get better prices for their homes during these times. The same types of supply/demand imbalances occur with stocks as well, so it can be useful to analyze the composition of various types of investors in order to gauge the impact on prices.

Demographics is one of the most common ways to do this because it is not only an important determinant of demand for stocks but also a reliable one. Demographics affect demand because the value proposition of stocks, which are more growth-oriented than bonds, is stronger for working age people than it is for retired people.

As noted [here], "Large populations of retirees (65+) seem to erode the performance of financial markets as well as economic growth." The rationale is also fairly straightforward: "Middle-aged adults are the engine for capital market returns; they are in their prime for income, savings, and investments. And senior citizens contribute to neither GDP growth nor stock and bond market returns; they disinvest to buy goods and services that they no longer produce."

As Rob Arnott and Anne Casscells describe [here], "The simple mechanisms of supply and demand should lower the return on assets: A larger group of retirees than ever before will be selling to a proportionately smaller working population than ever before. So, what the retirees wish to sell will already be priced lower, in real terms, but the time they wish to sell it."

The authors continue, "These implications for capital market returns and prospective inflation (stated here in their strongest terms) stem from the most basic law of economics: Supply and demand must match. Prices are set to equate supply and demand; no policy choices can alter this relationship. Retirees demand goods and services; workers supply them."

Arnott and Casscells conclude, "The potential implications of our results are sobering," and indeed that may be an understatement. For starters, "The selling pressure, however, is not likely to affect all assets uniformly. Retirees favor some assets more than others. They tend to rely less on growth assets, such as stocks, and favor fixed income assets." As a result, the diminishing demand for stocks should start to affect the prices paid.

In addition, the effect on GDP growth and market prices is likely to be significant. As reported [here], “demographic factors alone can account for a 1 1/4-percentage point decline in the natural rate of real interest and real gross domestic product growth since 1980”. John Authers from the FT concludes [here], "This is a huge claim, as it implies that demographics — rather than fiscal or monetary policy, technology or other changes in productivity — are responsible for virtually all of the decline in economic growth over the past 35 years." In other words, the impact of demographics is large and there is very little that public policy can do about it.

Finally, the demographic impact should already be taking effect now. Arnott and Casscells note, "The ratio of retirees to workers begins to rise in roughly 2008-2010 and starts to soar around 2015." Given that markets tend to anticipate the future and that demographic trends are extremely reliable, "overt selling pressure on risky assets" should already be in process.

In an important sense then, the more interesting question is not, "Why has the market been down over the last few weeks?" but rather, "Why hasn't the market been selling off over the last several years in anticipation of demographically-driven lower demand for stock ownership?"

An unrelated story provides some interesting insight. I have been going through and reviewing some research files recently and came across the headline in the Financial Times [here], "Facebook backtracks on privacy." The article started, "Facebook has been forced to retreat on some changes to its privacy settings after the move created an outcry from data protection campaigners and left users confused and irate." None of it struck me as especially interesting except for one thing. The story was published on December 12, 2009, almost nine years ago.

This struck me as interesting because nothing in the content of the article came across as dated. Given the commonality in privacy issues with those raised by the Cambridge Analytica incident, the article could just have easily been written one year ago as nine years ago. The details were different, but in both cases the company displayed broad disregard for customer privacy. So why did it take eight years for the story to finally gain traction?

The answer to both questions, I believe, lies in one of the more interesting and unique aspects of this latest bull market run: The substantially increased share purchase activity by entities such as central banks and corporations. For example, I wrote [here] that "Billions and billions of dollars' worth of stock purchases by central banks have severely distorted those [market] signals." More recently, I noted [here], "Since share purchase activity is dominated by price insensitive share repurchases, stock prices reveal little information content about underlying economics. This helps explain why neither inflation fears nor trade wars nor emerging market chaos nor increasing rates have been able to rein in stock prices to any great degree." This applies to Facebook stock just as much as to the market as a whole.

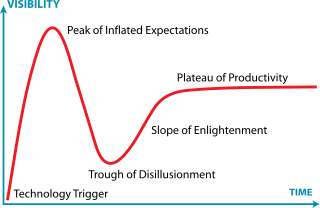

As a result, aging demographics is to stock demand as a slow leak is to air in a tire. Just a little bit seeps out each day such that you don't really notice it. If you regularly put more air in the tire, it can last quite a while. Over time you have to refill the tire with increasing frequency, though, until even with that effort, the tire cannot retain enough air to be safe.

This suggests that despite regular and significant "refills" of demand by central banks and corporations, it is only a matter of time before the "leak" of aging demographics will finally cause demand for stocks to fall short. As I noted before, "While high valuations may appear, superficially, to validate underlying economic strength, they are really just temporarily masking the darker reality of 'the relentless demographic tide of Baby Boomers rebalancing their portfolios away from equities and into bonds'."

Further, almost as if to add insult to injury, there is yet another trend that investors should keep their eyes on. Taxes are always an important investment consideration and the recent tax legislation may further hasten the retreat from stocks. As the FT notes [here], "Mr [Cory] Booker’s initiative [to create Opportunity Zones] was a little-noticed element of President Donald Trump’s 2017 tax bill. In simplest terms, it allows investors to reduce their capital gains by investing in deprived areas." Specifically, "The authors of the plan settled on a simple incentive: allow investors to defer capital gains — from the sale of property, stocks, a business, anything — as long as they reinvest the profits in one of 8,700 Opportunity Zones around the country."

In terms of the impact of the plan, the FT reports that views are mixed: "Proponents argue that Opportunity Zones may one day come to be seen as the boldest economic development plan for poor areas in a generation. But they could also end up presenting the most generous tax deal to the rich in decades." Reports suggest a wide variety of stock owners could be affected. James Nelson, of real estate broker Avison Young, predicts, "Opportunity Zones would become the method of choice for high net-worth individuals and family offices to make 'intergenerational' transfers of wealth." Daniel Barile, managing director at SkyBridge Capital, says his firm is "targeting the 'mass affluent' sitting on inflated stock portfolios after a long bull market and facing big capital gains taxes if they sell."

Regardless, the prospect of relief from capital gains taxes and its commensurate effect on demand for stocks seems to be the most predictable aspect of the legislation. By one account, many executives "were already salivating at what could be the biggest tax break of their lifetimes." The Economist noted [here], "Boosters point to the trillions of dollars of unrealised capital gains ready to be unlocked," in a story entitled, "Boondocks and boondoggles". As a result, anyone holding stocks that have appreciated considerably, whether they are interested in Opportunity Zones or not, needs to be aware that the plan is likely to further reduce demand for stocks. In other words, the leak in the tire just got bigger.

For investors who are making tactical decisions about whether to increase, maintain, or reduce exposure to stocks, then, it is important to consider the supply and demand of stocks. One aspect of such consideration is to realize that when you go to buy or sell stock, you are engaging with others who are doing the same. Stocks do not provide the same value proposition as bonds for retirees and as the proportion of retirees to workers continues to increase, demand for stocks will diminish. As prices increasingly get set by price sensitive buyers, it is quite likely they will need to be considerably lower in order to meet the increasing supply provided by retirees selling stocks.

In addition, the recent regime change in the market may well be, at least partly, an indication of the ongoing structural shift in demand. A piece by the FT [here] notes, "Taking advantage of weakness in US stocks, known as buying the dip, has stopped working for investors this year for the first time since 2002, in the latest sign that the bull run in under threat." Georg Schuh, chief investment officer for Emea at Deutsche Wealth Management described an important change in their strategy: "We are de-risking, moving from buying the dips to selling the highs."

Investors should also be attuned to the reality that regardless of evidence for structural shifts in demand for stocks, there will always be pundits making the case for remaining invested. For example, Citigroup's chief global equity strategist, Robert Buckland, wrote in the FT [here], "It still seems too early to call time on this ageing bull market", and specifies, "So our advice is to buy this dip." Not for nothing, this advice comes from the same company that told us back in 2007, "As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing."

Finally, there are also good reasons why more strategic holders of stocks may want to reassess their holdings. Many investors are told that stocks provide the best returns for long term investors, a thesis popularized by Jeremy Siegel with his book, Stocks for the Long Run, and one that has become almost a religious belief for many investors and advisors. As Grant's Interest Rate Observer (November 16, 2018) points out, however, a closer analysis of historical returns depicts the case for stocks as considerably more uncertain and less attractive than widely believed.

Enlisting the help of Edward McQuarrie, professor emeritus at the Leavy School of Business, Santa Clara University, Grants tells us, "Almost all the real price appreciation of the S&P 500 since the late 1920s occurred in the past 30 years, after the boom of the 1980s was well under way." For one, this implies that stocks can provide unexceptional returns for long enough periods of time to affect even long-term investors. In addition, since the 30-year period of strong real returns coincides almost perfectly with Baby Boomer peak savings years, one could argue that strong real stock returns depend primarily on favorable demographics. Insofar as this is the case, many investors may want to reconsider the role of stocks in their portfolios.

So, for investors who may be unsettled by recent market gyrations, and even those who aren't, evaluating the merits of stocks through the lens of supply and demand can provide useful insights. Many investors are focused on avoiding big "pot holes" such as an economic downturn, trade wars, and the like, which could cause stocks to go down quickly. The greater danger, however, may be the less visible "slow leak" of declining demand due to aging demographics which is just as effective at ruining a nice trip.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed