October 2015

Things definitely got more interesting in the third quarter as most major indexes were down noticeably for the first time in many years. At least as interesting as the rare occurrence of a downdraft was the breadth of pain it caused. It was devilishly difficult to avoid being harmed as evidenced by the poor performance of such accomplished investors such as David Einhorn and Leon Cooperman.

Cooperman complained [here], “In the world I grew up in, and the world Warren Buffett grew up in, when something went down you wanted to own more, and in the world that we’re in now, it goes up you want to own more and it goes down you want to own less, and that is just counterintuitive.” His frustration is indicative of just how pernicious this investment landscape is.

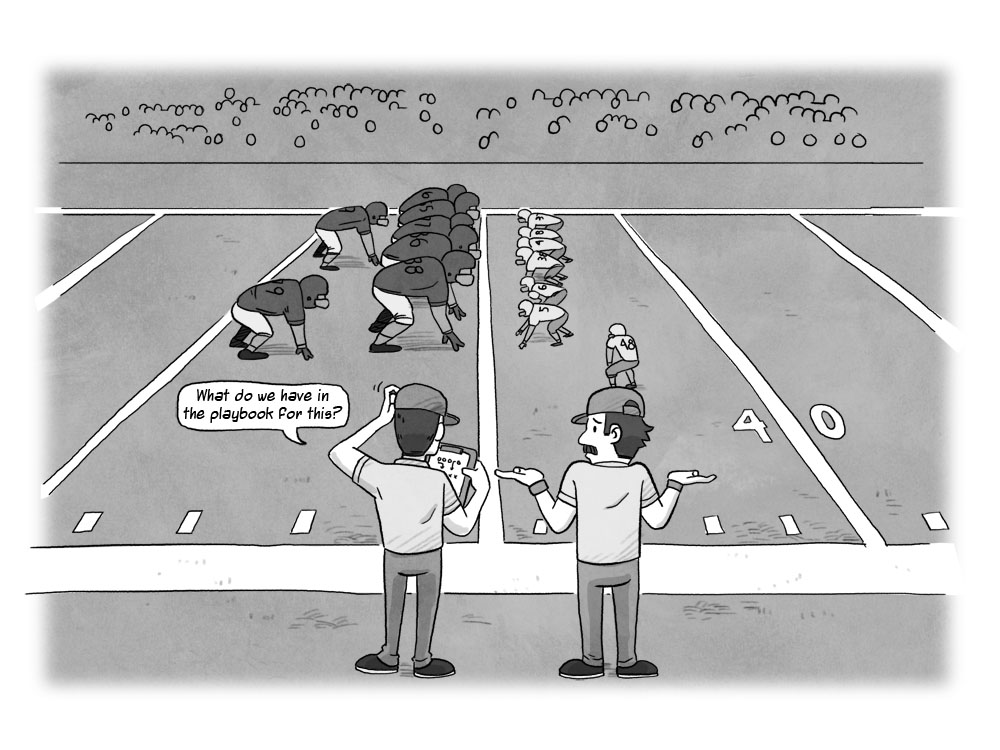

While it doesn't surprise us at all that the market was due for a breather after such a long and essentially uninterrupted rise, the tumult in the third quarter does seem to represent a change of some sort. Our assessment is that the explosion in global credit has reached the upper limits of its beneficial impact and now we are beginning to experience the unpleasant blowback. Insofar as this is correct, it will render many narrow investment approaches and conventional heuristics ineffective and will demand thoughtful new approaches. Since there are plenty of other important cross currents as well, it will be more important than ever to view the investment landscape in context: We are going to need a new playbook.

One of the old playbooks has focused on following the relationship between markets and the economy. The theory goes that since market prices are ostensibly the discounted sum of future cash flows of business enterprises, market prices will provide an early warning signal for recession. In the context of monetary policy that has the stated goal of inflating asset prices, however, the informational content of market prices becomes severely degraded which makes their use as a signal considerably less useful.

This isn't to say that there are no longer useful leading indicators, there is just a less robust set than we used to have. Those that we weight more heavily are pointing down. In his typically thoughtful and eminently logical analysis, John Hussman discusses this subject in his recent weekly commentary [here]. In order to isolate what would cause a business to increase its activity, he looks to its "production pipeline" which can be represented by "new orders and order backlogs that can’t be filled out of existing inventory". Based on the evidence that the "order surplus" is deteriorating, near term economic activity appears likely to be weaker.

Another playbook that blossomed after the financial crisis was simply to ride the wave of central bank liquidity. While the strategy was always imperfect in that monetary policy was never going to solve any of the fundamental problems revealed in the financial crisis, it did buy some time. The continuance of extraordinary monetary long after emergency conditions passed and the eventual adoption by most central banks around the world signaled the intent that central banks wanted to keep asset prices buoyant. While we were somewhat surprised that central bank policy remained so easy for so long, especially when considering the increasingly obvious costs of doing so, we have been even more surprised that markets have failed to protest.

That is until the third quarter. After over five years of nearly perfect correlations between central bank assets and asset prices, the strategy of following liquidity abruptly hit a wall. A poignant example from zerohedge shows that from 2009 until early this year, there was a direct correlation between central bank purchases and high yield spread changes, but those two data series diverged sharply this year [here]. It does appear as if the relevant question has changed from what central banks intend to do, to what can they do?

Perhaps the potential for monetary policy to diverge, with the Fed leaning towards increasing rates and the rest of the world continuing to ease, shook things up. Perhaps we are experiencing the effects of investors who have clung on to overpriced assets and now need an exit strategy just as liquidity is drying up. Perhaps we are just starting to experience payback time for an extended period of monetary profligacy. Most likely, what we saw in the third quarter is the confluence of all of these factors.

Certainly all of these factors were involved in the developments in China and other emerging markets over the summer. As Gillian Tett reports in the Financial Times [here], "it is becoming clear that emerging markets have become caught up in a new credit bubble." One thing that has changed this time around is that the numbers now are much larger. Tett notes, "But as the IMF notes in its latest financial stability report, between 2004 and 2014 emerging market corporate debt increased from $4,000bn to $18,000bn, with much of the growth occurring after 2008."

She also dispels any doubt about the destination of increased liquidity: "Citi has tried to calculate global private-sector money creation and reached a startling conclusion: three quarters of all global private money creation in the past five years has occurred in emerging markets." Finally, putting the developments into perspective, she notes, "Overall, the IMF calculates that emerging market liabilities are now twice the size of their equity; a mere four years ago, they were at par." Clearly a lot of money flowed into emerging markets without respect to weakening balance sheets.

Of course this movie has played before and Michael Pettis provides an excellent description of the paradigm of credit booms in lesser developed countries (LDCs) in his book Volatility Machine: "In each case, first there is some displacement that sets off a liquidity expansion in the major capital exporting countries, which is followed by the lending and investment boom in the LDC markets and, usually, a spurt of growth. At some point there is the second, usually external, shock that causes a rapid tightening or a sudden collapse in market liquidity in the major money centers. The local LDC boom quickly ends, and payment difficulties begin."

The problem is a simple one, but nonetheless, one that still tends to recur. John Dizard explains in the Financial Times [here], "foreign currency borrowing is not the economic original sin for developing countries. That would be 'malinvestment', or using the proceeds of any capital markets activity, official or private, foreign or domestic, for non-productive purposes." Or as John Burbank of Passport Capital puts it in zerohedge [here], "The wrong people got the capital — emerging markets countries and corporates and a lot of cyclical companies like mining and energy, particularly shale companies — and this is now a major problem for the credit markets." Not surprisingly, there is always a contingent of people who are more eager to receive money than they are capable of putting it to good use.

One of the things that Pettis captures so well in his book is the mechanism by which LDC credit bubbles unwind. As he describes, "It is the structure and behavior of market players that systematically undermines the market, not changes in fundamentals. These only set off the crisis." Or, as he rephrases it later, "Their behavior is not a matter of psychology, panic, or herd mentality but rather a forced need to close out a losing 'speculative' position." The important lesson is to avoid the tendency to view the unwinding of emerging market credit bubbles as being driven primarily by faulty human decision making that can be exploited; they are not. Once the unwind starts, it proceeds mechanically until positions get closed out.

The analysis of emerging market credit reveals some important changes in the investment landscape. For one, it highlights meaningful limitations to Fed policy. As Henny Sender notes in the Financial Times [here], "It is not so much that the Fed has lost credibility as that its actions now matter less. Monetary policy that acts only on financial asset prices eventually loses its power. More importantly, the Fed matters far less for world growth than China does." Further, the scale of emerging market debt now challenges the capacity even of developed countries. Tett summarizes, "But Mr. King of Citi doubts this will work: the emerging market bubble is so big that it is far from clear central banks could plug the gap if (or when) this money creation slows down." Further, given the scale and interconnectedness of markets, John Dizard concludes ominously, "Instead, we are more likely to have longer, more complicated disasters."

At the same time that we have a significant need to deal with these very serious issues, we also find ourselves handicapped in our ability as investors to respond. The general trend towards creating tradeable securities out of indexes and measures, what we call "financialization", as well as the infrastructure that accompanies these activities, has had a big impact on market conditions. The widespread ability to trade almost any phenomenon, in combination with low rates which make it virtually costless to gamble, have created an environment in which long term investing has given way to short term position taking and in doing so, has made the financial ecosystem considerably less robust than it used to be.

One of the important consequences of the trend towards passive investing is that there is simply less information in market prices than there used to be. Ren Cheng from Fidelity describes this beautifully in his piece "Acting and Passive Investing" [here]. He describes that passive strategies "create liquidity in financial markets, but inject no information about companies into the markets." Conversely, active strategies "create information that leads to disparate investment decisions." Cheng concludes that "the increase in market share of passive strategies during the past decade has diluted the amount of information in the marketplace." This trend can hurt investors by making market prices dubious sources of information, but it does imply important future opportunities for active investors.

Another phenomenon that has emerged coincident with extraordinary monetary policy is that asset correlations have remained extremely high. Gillian Tett recounts [here], "as the IMF chart [page 22 of the latest IMF financial stability report] shows, something rather bizarre is happening now. Between 1997 and 2007, the level of correlation between the major asset classes was around 45 per cent." She continues, "During the crisis of 2008-2009, correlation jumped to 80 per cent." This experience is typical; correlations typically rise in times of crisis.

She continues, though, "What is fascinating is the experience of the past five years. Since 2010, the sense of market crisis has ebbed and many asset prices have soared. But correlation has not fallen, as in the past; instead, it has averaged about 70 per cent, almost twice the pre-crisis level." The implication could hardly be more important: The utility of diversification, the tool by which most investors try to manage risk, has been vastly diminished over the last eight years. The lesson is: investors should not count on diversification to be nearly as effective in easing the pain of the next downturn.

Finally, liquidity conditions have worsened due to regulation, systemic trading, and monetary policy itself. The situation is described well in a report from zerohedge [here]. One assessment from the report is that, "central banks’ distortion of markets has reduced the heterogeneity of the investor base," and that "this creates markets which trend strongly, but are then prone to sudden corrections." This explanation seems at least somewhat plausible because it also consistent with the observation of increasing correlations. The report continues, "We argue in contrast that the risk of illiquidity is spreading from markets where it is traditionally a problem, like credit, to traditionally more liquid ones like rates, equities, and FX." In other words, equity investors should consider themselves forewarned.

In conclusion, we believe we are in a uniquely difficult investment environment that warrants a great deal of caution. Investors are caught between a policy regime that is capricious, increasingly conflicted, and with diminishing capacity to effect desired outcomes on one side. On the other is an investment landscape in which information is diluted and for which precious little protection is available in the form of diversification. The precariousness of the landscape in the third quarter was captured well in a Financial Times piece [here], "The only thing that seemed to work was cash. Of course that's the one thing they [the hedge funds] don't have."

One of the key points to take away from this assessment is to recognize that in many important respects, the "game" of investing has gotten more difficult for the time being. Many conventional playbooks are not going to work the same way as they have in the past. Further, we are also going to be constrained by having fewer reliable landmarks by which to orient ourselves and less effective defensive maneuvers by which to protect against downside. Such an endeavor is going to require ongoing effort and a widespread awareness in order to navigate unfamiliar territory under adverse conditions.

The net effect, and one that is too rarely broached in this industry, is that it may well make sense for many investors to re-evaluate to what extent this "game" of investing is even worth playing right now. Although there are some reasonably attractive pockets, overall, it is tougher to win and easier to lose under these conditions. Importantly, there is no indication that this is a permanent state of affairs and we fully expect better opportunities in the future. At very least, investors should make absolutely certain that the rewards are worth the risks here, that expectations are realistic, and that the duration of your investments matches your investment horizon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed