February 2015

Saving for retirement is a high quality problem; it is certainly far better than not having the means to save at all or being so pessimistic about the future as to forego the effort entirely. There is no doubt that good progress has been made; the 70th anniversary issue of the Financial Analysts Journal, for example, is a wonderful compendium of the many useful ideas that have emerged over the years.

Despite these advances, the 70th anniversary retrospective also reveals just how far away we are from any kind of ultimate solution to the retirement challenge. More and more burden is falling on individuals and small institutions to understand complex investment topics and to make difficult choices at a time when they often have very limited resources. It would be challenging enough to confront extremely disparate investment possibilities if investors could get a clear picture of the landscape with the help of high quality information and insights. Unfortunately, that is rarely the case.

A number of impediments to good information flow have been around and just require some effort and expertise to filter through. One problem crops up simply because most human beings are just not wired to pick up on certain types of change. As Eric Beinhocker noted in The Origin of Wealth, "The punctuated nature of change in complex adaptive systems is almost perniciously designed to lull our pattern recognizing, full-building minds into a sense of stability and then hit us with big changes." As a result, "big changes" tend to elude those who are not aggressively on the lookout for them.

The difficulty of picking up on "big changes" is often exacerbated by organizational tendencies toward incrementalism. Beinhocker continues, "Firms tend to be organized as hierarchies, with the people who are the most experienced sitting at the top. This arrangement presents a tradeoff: the mental models at the top are likely to be some of the best for the purposes of execution in a stable environment, but less capable of exploring, and less likely to adapt to environmental shifts." These tendencies can bias many sources of information that investors rely on and these biases can even extend to the use of metaphors as mentioned the last blog [see here].

Organizational characteristics can impede the presentation of good information in other ways too. Lee Buchheit, the pre-eminent lawyer for helping countries restructure their debt, noted in a Financial Times piece on public finance [here] that, "The one common factor in every country he has worked is initial denial." He continued, "They all realised far too late the extent of their problems ... And when they did it was too late to arrange an orderly readjustment of the debts." The lesson is that in many cases large organizations may disseminate bad information simply because they don't know what is going on -- because they are in denial.

It is also important to keep in mind that "information" may mean different things to different parties. John Kay reported in the Financial Times some time back [here] of his experience as a consultant: "People did not use our models to help make decisions, but to justify decisions they had previously taken." He continued, "The modern world of business and politics is plagued by spurious rationality and bogus quantification ...The desire to do what is right is overtaken by the necessity to do what is easy to defend."

"Spurious rationality and bogus quantification" pose two risks to investors. As Kay concluded, "Bureaucracies engaged in self-justification frequently mislead themselves -- more often, perhaps, than they mislead the public." Complex models and busy presentations can deceive not just investors, but their creators as well. It is normally fairly hard to tell if someone is lying, but it is much harder yet when they think they are telling the truth.

The challenges to accessing good investment information have really escalated since the financial crisis, however, when it became obvious that most of the large banks either didn't know or didn't care about the risks in the financial system. In the wake of the crisis, investors with the means began reconfiguring their sources of information accordingly. Ultra high net worth investors shunned banks and advisers out of distrust of conflicts of interest and instead sought to share more information with one another (whom they could better trust). Many larger institutions started relying more on their active managers to provide useful insights into the markets.

While this evolution in behavior doesn’t help individual investors or small institutions directly, it does highlight the importance of adapting to a changed investment landscape by rethinking information sources. As such, it is useful to explore some of the developing problems with existing information channels.

For one, a global economic landscape plagued by high levels of debt, demographic weakness, and geopolitical tensions certainly creates incentives for some parties to take liberties with the truth. Ben Hunt described this change in his article, “Stalking Horse” [here]. He concluded that, "When words are used for strategic effect rather than a genuine transmission of information you create a virtual stalking horse ... Unfortunately, I believe that is exactly what has happened, that 'strategic communication policy' [on the part of the Fed] has mutated from an emergency measure designed to prevent an economic collapse into a standard bureaucratic process designed to maintain financial stability." In other words, the Fed, one of the more respected financial institutions because of its independence, now seems to be forsaking the "genuine transmission of information" for other purposes.

Regardless of the possible merits of such a direction, subordinating the "genuine transmission of information" to other goals comes with a cost. That cost comes in the form of the market, which depends on decent information for price discovery, becoming progressively more uncoupled from true economic fundamentals. Distorted signals make it extremely difficult for investors to judge investments on their merits and that creates extremely high levels of "regime uncertainty". Needless to say, such conditions make it extremely difficult to adequately weigh risk versus reward.

The information challenge is further complicated by the fact that many investors also seem to be handicapped by a condition called "indefinite optimism" by author and entrepreneur, Peter Thiel. According to Thiel in Zero to One, "The strange history of the Baby Boom produced a generation of indefinite optimists so used to effortless progress that they feel entitled to it. Whether you were born in 1945 or 1950 or 1955, things got better every year for the first 18 years of your life, and it had nothing to do with you ... A whole generation learned from childhood to overrate the power of chance and underrate the importance of planning." While this obviously falls far short of describing every individual born during the baby boom years, it does go a long way in capturing a dominant sentiment of the generation.

With this as background, Thiel describes, "To an indefinite optimist, the future will be better, but he doesn't know how exactly, so he won't make any specific plans. He expects to profit from the future but sees no reason to design it concretely." As a result, a number of investors fail to get good information simply because they have some general sense that they don't need it, that things will just work out. Worse, a disproportionately large group of indefinite optimists are also sources of investment information; they are leaders of investment firms, businesses, government, media, and advisory firms. As authoritative as these folks may sound, far too often their positions fail to withstand analytical scrutiny.

In any investment environment it is critical to get good information such that potential rewards can be accurately traded off against risks so that the entire proposition can be well understood. On this count, unfortunately, things have gotten worse for investors and are not likely to get better any time soon. Gillian Tett noted in the Financial Times [here] recently that "Most ordinary people have no idea what central banks are really doing with their trillion-dollar experiments," and she makes a good point. Such radical policy actions should come with clear explanations including the risks. Failing to do so is being complicit with misinforming the investing public.

Given the swirling winds of misinformation, there are a couple of actions investors can take to protect themselves. For one, the timeless piece of investment wisdom, "If you don't know exactly what is going to happen, then don't invest as if you do," serves as a useful guide. In other words, if you don't have extremely strong evidence of specific outcomes -- such as much stronger economic growth, then don't invest as if you do. If you don't know absolutely that interest rates will remain extremely low over your entire investment horizon, then don't invest as if you do. If you don't know how massive debt levels will be paid off, then don't assume they will be.

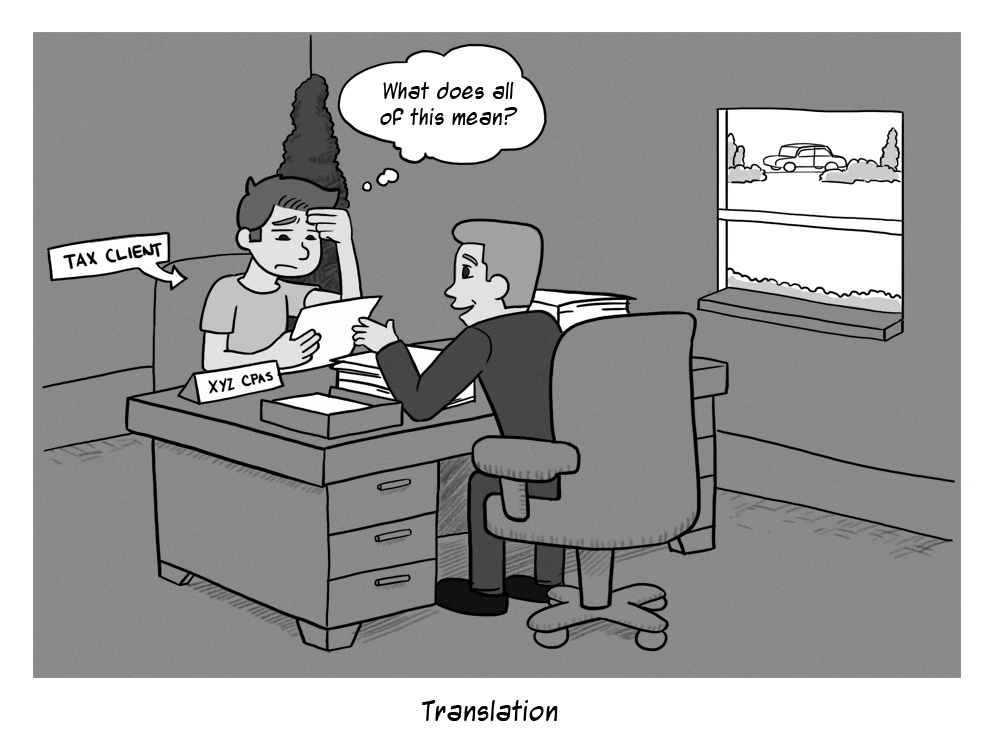

At such times, it is also enormously useful to have access to investment expertise that can help filter and interpret information signals and to translate them into insights that are meaningful for you. Just as we often rely on an accountant to review our masses of financial information in the context of vast and constantly changing tax laws, so too should we be able to find, and rely on, investment experts. Unfortunately, the investment industry as a whole has not done a good job of serving clients’ best interests and indeed has fallen victim to too many of these informational challenges itself. It needs to change if investors are going to have a fair chance to save for retirement.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed