Doing so, however, diverts attention away from the reality there is absolutely nothing deterministic about inflation. This is actually a fairly useful revelation since it implies investors will have a very different landscape to navigate.

Inflation rage

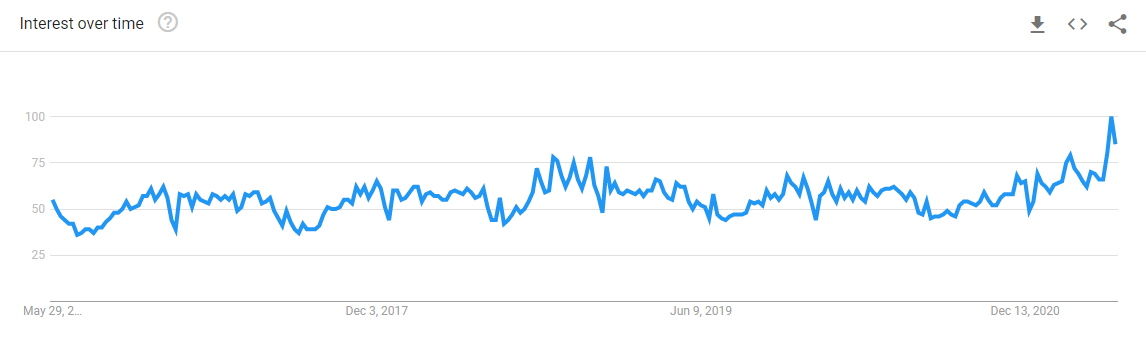

The graph for the search term "inflation" on Google Trends paints a thousand words. Anchored in a well-defined band for most of the last five years, inflation started piquing interest early this year and really shot up in the last few weeks.

There have certainly been a number of contributing factors: Extremely loose monetary policy seeded concerns and a slew of anecdotal reports of price increases and a hot CPI number on May 12 helped confirm them. Another important factor, described by Bloomberg's John Authers, is the symbiotic relationship between media content and audience interest. In other words, journalists write about subjects for which their audience has interest and that creates a self-reinforcing loop:

"Inflation is the topic of the moment. Some cynics can argue that it’s only such a big deal because I and other journalists have made it so. But judging by the number of Bloomberg clients who fired in questions for the live blog Q&A session we held on the terminal Tuesday, there is quite a lot of interest out there in the financial markets. And it is the interest in inflation from investors and other consumers of financial journalism that prompts people like me to write more about it; we have the perfect example of reflexivity, in which perceptions can change reality."

The heightened level of interest in inflation has spawned quite a few debates about inflation. I outlined some of these in a previous blog post but William White provided excellent context at John Mauldin's Strategic Investment Conference (SIC). Even before the pandemic hit, he described, the economy had "morbidities", the most of important of which was the excessive accumulation of debt relative to economic output. Since "those morbidities are still there", White expects debt pressures to win out and induce deflation in the medium-term. After that though ...

"Longer term, if the stagnation continues, I suspect what will happen is the governments will throw everything they can at it. Which is, they will double down on both fiscal and monetary. And this is where the problem arises. And we've seen this many times in history and we've got good theory to try to explain it, what happened is that in that kind of an environment where you've got big government deficit and a very large government debt and growing recourse to the central bank, as the only group of people still left that will lend money to this government. At a certain point, the fear of fiscal dominance creeps in, and the minute the fear of fiscal dominance comes in, the central bank will do anything to keep this government afloat."

Policy and politics

This is a point very much corroborated by Karen Harris of Bain & Company at the SIC. As she and her team assessed "the biggest most lasting scars of COVID-19", they revealed, "the most striking is the step change in what is considered acceptable intervention in an emergency and the lower bar for what constitutes an emergency." In other words, the threshold for "throwing everything they can" just got lower while the "everything" got even bigger.

An interesting element of White's analysis is nowhere does he mention CPI, money supply, or any kind of economic equation. Indeed, this dovetails with Martin Wolf's recent thinking in the FT:

"Milton Friedman said that 'inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon'. This is wrong: inflation is always and everywhere a political phenomenon. The question is whether societies want low inflation. It is reasonable to doubt this today. It is also reasonable to doubt whether the disinflationary forces of the past three decades are now at work so strongly."

With inflation being primarily a political phenomenon, then, it makes sense to scrutinize the politics more carefully. Jonah Goldberg provided useful insight into such matters with a recent piece about the Republicans' removal of Liz Cheney from leadership:

"But the idea that this [Cheney's removal from leadership] was just a tempest inside the beltway tea pot strikes me as profoundly wrong. History is a bit like one of those choose-your-own-adventure books. Small decisions that seem trivial move events, people, and institutions along paths that lead to more choices while simultaneously foreclosing other choices. If you’ve ever read a book about the lead up to World War I, you know this."

"Think of it [Cheney's removal] like dynamic scoring. This decision will have multiplier effects. The closet normals will become Trumpier, and some of them will follow the path of Graham and stop being normals at all. This event will make it harder to reject the next crazy thing Trump wants or says. Elise Stefanik will fulfill her mandate to signal that the GOP is Trump’s party, full stop."

A view of increasing political tension was corroborated by a Financial Times update on infrastructure talks in Congress. In vowing to obstruct efforts by Democrats to raise taxes to pay for infrastructure, Mitch McConnell declared:

“This [tax increases] will slow the economy down to a crawl, and I think our chances of stopping it . . . are pretty good,” he told Fox News. “They may be able to pull it off, but I think it is going to be really hard, and we are going to fight them the whole way.”

Pulling it together

So, where does all of this leave us? In a superficial sense, not very far. We might get deflation, we might get inflation, we might get both. In a complex adaptive world, it is just hard to say how things will turn out.

While this is all true, it is too cynical a view. As Rusty Guinn from Epsilon Theory highlights, the uncertainty and variability implied by such a landscape has its own set of implications:

"What that narrative [Which direction are prices going?] misses, however, is the importance of sensitivity to price volatility in a path-dependent world. If you think that what’s happening in auto supply/demand and pricing is generally good for auto dealerships and the related industry infrastructure, you are probably right. But there will also be leveraged dealerships who participate heavily in inventory acquisition at prices and quantities that they can’t turn over before the pricing environment flips back. There will also be winners who figure out how to accommodate and navigate higher used price expectations in trades for new vehicles."

In addition, since price volatility increases the overall riskiness of doing business, an inflation “premium” will be incorporated into discount rates by the market. One lesson learned from the inflation of the 1970s and 1980s is higher levels of actual inflation also expand the distribution of expected inflation. After several decades of extremely low actual and expected inflation, the emergence of an inflation “premium” can increase discount rates whether inflation roars in full fury or not.

This hints at a final point. Although we may not know the future path of inflation, we do know something useful: Inflation is likely to be much more volatile than it has been the last three decades. As such, investment strategies built on a foundation of stability and disinflation are unlikely to prove nearly as fruitful. Indeed, an environment of heightened volatility demands very different portfolio construction than what has worked in the past.

Conclusion

Much like there is nothing inherently wrong with different types of weather, the challenge comes when it changes dramatically, and one isn’t prepared. A shocking example happened during a recent ultra-marathon event in China. When a cold spell trapped runners on a mountain twenty-one of them died from exposure. While this is obviously an extreme example, it highlights the importance of being prepared when the environment can change quickly.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed