March 2015

The market for public stocks has changed so much over the last 30 – 40 years that many aspects are barely recognizable any more. Thanks to declining pension plan coverage, advancing technology, proliferating index funds, and plenty of other reasons, far more people own stocks now. This massive broadening of stock ownership also created a boom for third party investment management which, given the amazing growth prospects, was often built on the model of a "net" designed simply to catch as much demand as possible. The unfortunate consequence for investors has been that just as they have had to accept much greater responsibilities for managing funds for retirement, they have also been challenged with a mind-boggling array of investment choices.

The good news in this story, for smaller investors, is that they are also unencumbered by the inertia that plagues so many large organizations -- including investment firms. The greater inherent flexibility of smaller investors could well prove to be an important advantage in coming years. It's no secret that larger firms tend to thrive in more stable environments in which they can standardize processes, cut costs, and benefit from scale. But this modus operandi has its drawbacks. As Eric Beinhocker notes in The Origin of Wealth, "A good aspiration provides a powerful motivating force to keep the company in constant motion, trying new things, and supporting the ethic of experimentation. In evolutionary systems, stasis on the fitness landscape is a recipe for extinction -- if you ever stop experimenting and moving, you're done for." Whether you are an individual, a company, or an organization, the point is the same: Not only does adaptability provide an advantage, but lack of adaptability is a "recipe for extinction".

Now, imagine a world in which many of the assumptions that underlie economic and market orthodoxy become seriously challenged. Imagine that a tipping point is reached and that change occurs, as it sometimes does, in dramatic and nonlinear ways. In such cases, large, established firms that are driven by static business models and are resistant to change are likely to fare very poorly. Conversely, investors who are open to "try new things" could actually reap significant advantages in managing through the changes. Indeed, these imaginings are less than completely hypothetical; many popular assumptions about the economy and the market are artifacts of a bygone era that could well prove dangerously misleading.

One assumption that will become increasingly challenged is that of strong economic growth. Most developed economies as well as many emerging economies are likely to produce slower economic growth in the future. The causes are simple enough to isolate and they really boil down to demographics. Rob Arnott and Denis Chaves noted in their 2012 research piece on demographic changes [here], "One common theme emerges ... Large populations of retirees (65+) seem to erode the performance of financial markets as well as economic growth." Since, as Jim Paulsen at Wells Fargo notes, "World War II synchronized demographics," these pressures are being felt broadly across the globe.

For those predisposed to "believing" in stronger economic growth, some common counter-arguments fall short. First, it is unfair to dismiss the same demographic trends that have so clearly boosted demand historically as being immaterial when the pendulum swings back. From retail shopping to consumer credit to housing, the baby boom generation has fundamentally changed the economic landscape by boosting demand for a wide variety of consumer goods and services. As Harry S. Dent notes in The Demographic Cliff, the logic is pretty simple: "Young people cause inflation. Why? They cost everything and produce nothing ... Conversely, older people tend to be more deflationary. They spend less, downsize in major durable goods, borrow less, and save more." Just as baby boomers amplified consumer spending in their peak spending years, so too will they hinder consumer spending in their lower spending years.

Another argument made for stronger economic growth is technology. It is true that technology can boost productivity and economic growth over time as Robert Solow illustrated with his economic growth theory. Even Solow acknowledges [here], however, that there can be a significant lag between the introduction of technology and sufficient enough penetration to noticeably improve productivity. As a result, while improved technology may positively affect productivity, its impact is normally delayed, spread over a fairly long period of time, and unlikely to overwhelm demographic forces.

A second assumption that will become increasingly challenged is that debt levels are not a problem. This position is rarely defended with any degree of analytical rigor but rather tends to represent a vague and cavalier notion that debt has not caused a problem yet so it must not be an issue. A hard look at the numbers, however, reveals a very different picture. Harry S. Dent provides such a look in The Demographic Cliff and comes up with total debt and liabilities of $127.5 trillion. That number is comprised of $61.5 trillion in debt among households, companies, financial institutions, the federal government (as reported by the St. Louis Fed), and net foreign debt. It also includes estimates for unfunded entitlements of $7.9 trillion for Social Security, $22.8 trillion for Medicare and $35.3 trillion for Medicaid.

For perspective on such an unbelievably large number, the $127.5 trillion sum is more than eight times GDP and represents about $400,000 for every US citizen, or about $1 million for every US household. One distinctly possible consequence of unwieldy debt burdens is that not all of them will be paid in full. We shouldn't be at all surprised to see most if not all avenues taken in the future to contend with these liabilities. Many pensions and entitlements will be reduced. Many debts will have to be written down or written off. People will have to work longer and retire later. There will be pressure to raise taxes. And the uncertainty of the manner and degree in which these challenges are addressed are likely to cause a great deal of uncertainty. In short, the magnitude of indebtedness is so extreme that much of the burden will fall on younger and future generations.

The looming burden of managing such overwhelming debts invites a challenge to another common assumption, that of the stability of the dollar. The assumption that the money we transact with and get paid with is stable is such a fundamental one as to normally escape our consideration on a day to day basis. With the exception of a pretty nasty bout of inflation in the 1970s, the majority of today's investors have virtually no experience in managing businesses, personal finances, or investing in an environment of significant inflation. Inflation doesn't have to be excessive or imminent to cause harm either. Even at a relatively low level of 2%, the current Fed target for inflation, a dollar loses more than half of its value over a forty year investment horizon. In other words, it matters a lot to long term investors.

Further, just as with demographics, recent historical lessons may be materially misleading in regards to the dollar as well. For one, the relative strength and stability of the dollar through 1971 was associated with massive economic growth and the emergence of the United States as an economic and political superpower, a trajectory unlikely to repeat. In addition, it also was linked to gold during that period which provided a strong foundation. The period since gold convertibility was terminated in 1971 is, in the greater context of history, a fairly recent experiment with purely fiat currency. As such, the dollar's relative stability since then is much less evidence of its inherent soundness than of fortuitous circumstances and its relative attractiveness.

While inflation is not an immediate scare, for those of us peering out over a long investment horizon on the lookout for danger, there are plenty of storm clouds to be seen. As Grant Williams describes [here], "When Nixon closed the gold window on August 15, 1971 ... he also ensured that credit creation would become as easy as just saying 'yes'." According to Williams, "What has changed since 1971 is the soundness of money," and he continues, "Today's disengaged society just makes the task of debasing a currency that much easier." In addition, as excess reserves at the Fed have ballooned since the financial crisis in 2008, so too has the potential for rapid money creation when lending does pick up. Finally, following the Fed's lead, central banks all over the world are now competing to weaken their currencies for the sake of gaining even a transient boost for their economies. All of these factors point to increased currency instability and bode poorly for paper currencies.

One last assumption, at least for purposes of this article, is that the market functions fairly smoothly and does a pretty good job of determining accurate prices for securities. As Michael Lewis described in Flashboys, however, "The 1987 stock market crash set in motion a process -- weak at first, stronger over the years -- that has ended with computers entirely replacing the people." Things haven't stopped there though. Ben Hunt notes [here] that "Over the past five to ten years, there have been three critical advances in computer science that have created extremely powerful machine intelligences utilizing a compound eye architecture." In short, machine intelligence dictates much of market liquidity. As Lewis assesses, "The world clings to its mental picture of the stock market because it's comforting; because it's so hard to draw a picture of what has replaced it; and because the few people able to draw it for you have no interest in doing so."

There are serious consequences to harboring antiquated perceptions of how the market works. The machine intelligences that comprise the market can act and react in tiny fractions of a second which can create liquidity events on the same time scale. The "flash crash" of May 2010, for example, was not a single, isolated glitch that was corrected and done with. Rather, there have been countless mini flash crashes which haven't made headlines, but are indicative of the same structure and the same risks. Since the market no longer works on "human" time, there are no longer the same opportunities to react to events or to gradually adjust. So when you are trying to figure out the right time to sell, remember what (not who) your competition is.

In conclusion, many aspects of the economy and the markets have changed a great deal over the last 30-40 years and this will have significant ramifications for the next 30-40 years. Recent comments by Mohamed El-Erian to the CFA Society of Boston [here] capture the new landscape well. These changes are so fundamental that according to El-Erian, "Outcomes – not just for investments but in a broader sense – are no longer normally distributed." As a result, many of the assumptions and lessons of the intermediate past will no longer prove useful. Robert Huebscher reports, "He [El-Erian] predicted that people will react in one of four ways when faced with a bimodal distribution: they will have a 'complete blind spot' and fail to recognize the distribution; they will average out the extremes; they will succumb to inertia and rely on recent history of events; or they will recognize that they have to do things completely differently. The first three groups will get things completely wrong, he said, and only the fourth group has a chance of success."

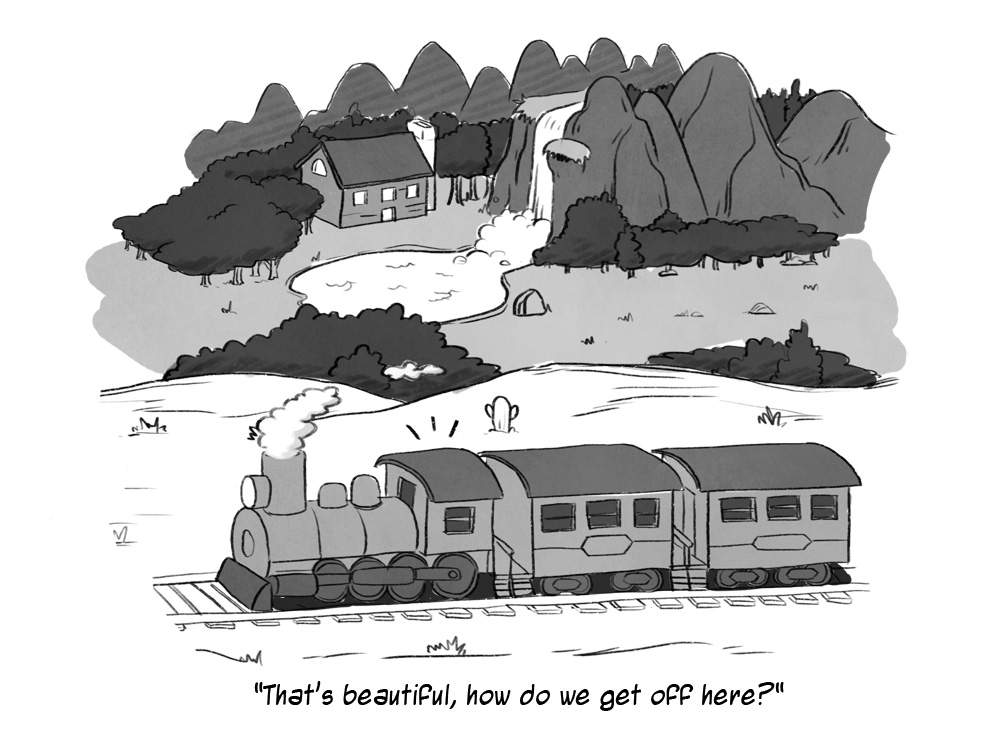

Such an ominous indictment to the status quo actually bodes well for those who are flexible and amenable to change. If you are willing to "try new things", you will have a much better chance of “hopping off” of conventional approaches and adapting to what are likely to be some momentous changes. Conversely, inflexible individuals and organizations will struggle because their models and playbooks won't work any longer. They will be like trains headed down the track: unable to overcome inertia and unable to change direction. In short, many will be stuck pursuing only what they know best, which in a different environment may well be a "recipe for extinction."

In addition to challenging old assumptions, investors are likely going to need to adopt some new approaches in order to meet their retirement goals. At very least it is likely that many people will need to spend more time and effort on their investment activities. Due partly to having greater responsibility for making retirement provisions, partly to needing to minimize costs, and partly to ensuring investments are well aligned with goals, many investors will need to become more engaged in the investment process. Some will certainly view increased engagement as an unwelcome incursion of free time, but others are likely to derive reward from more closely engaging with and guiding their investment plans in much the same way that many enjoy gardening.

One other thing investors will need to change is to find better investment advice. While the investment industry has done a phenomenal job of growing and of proliferating products, it has been far less successful in actually making investors better off. This isn’t to say that meaningful strides haven’t been made, it just means that there are still gaping holes in what is required vs. what is provided. Unfortunately, most high level investment expertise is currently bundled with asset management fees, if it is available at all. This is like having a serious medical concern and only gaining access to a doctor by paying an annual retainer of 1.5% of your assets. Investors need better access to high level investment expertise: professional investors who are willing and able to answer difficult questions, resolve dilemmas, interpret new trends, make sense of all the data and do so in a way that is understandable and personalized.

Investment times are a changin’ and just as we are seeing in so many other aspects of our lives, many past practices are no longer sustainable or desirable. In their place will emerge new practices that are better suited to the new environment. While change can sometimes be unsettling, sometimes it can be fun, interesting, and sometimes it ends up making things a lot better.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed