After solid performance in both July and August, the S&P 500 was considerably weaker in September. It was more than just passing weakness, however. The stock market looked much less the cocksure prize fighter than the contender who took a shot to the jaw that wobbled his knees.

There are plenty of explanations for the market’s diminished presence. Oil prices have remained stubbornly high. GDP estimates are coming down. Stagflation is a common topic again. The problems with real estate debt in China are metastasizing. Perhaps most importantly, rates are going up again, and because of inflation concerns, not better than expected growth. This witches brew may be entertaining for those caught up in the Halloween spirit, but long-term investors are wondering if this will bring trick or treat.

Rising prices

Much of the concern starts on the energy front where prices from oil to natural gas to coal have all been on the rise. The outstanding question is, “How much should we make of this?”

Robert Armstrong from the FT caught up with Jason Bordoff, the director of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, to provide some context on energy prices:

“The only thing that helps the climate is if demand falls with supply. Demand falls because of policy, and because technology drives the costs of the alternatives down, and capital goes into them. Some will say higher [fossil fuel] prices are what causes higher investment in alternatives. But they are going to cause a backlash against the climate policies that we really need.”

“What this [crisis] shows is how difficult, disruptive and messy this transition is going to be. Whoever thought we could replace the lifeblood of the world economy and that would be easy? It’s going to be super volatile.”

Slowing growth

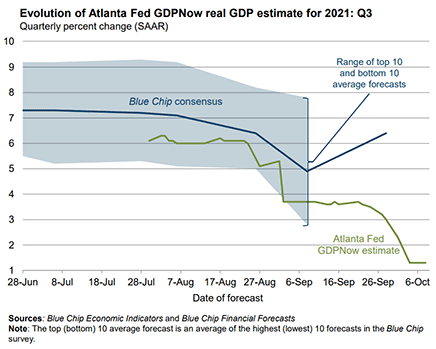

At the same time, GDP estimates for the third quarter have been falling precipitously to where the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate is only 1.3%. Not only is this a striking change from only six months ago, the deterioration in the last month has been substantial. Are higher energy and food prices already constraining other spending?

“Having already suffered the fastest drop on record, Chinese junk bond markets - where property developer issuers dominate - were routed once again as fears about fast-spreading contagion in the $5 trillion sector, which drives a sizable chunk of the Chinese economy, continued to savage sentiment.”

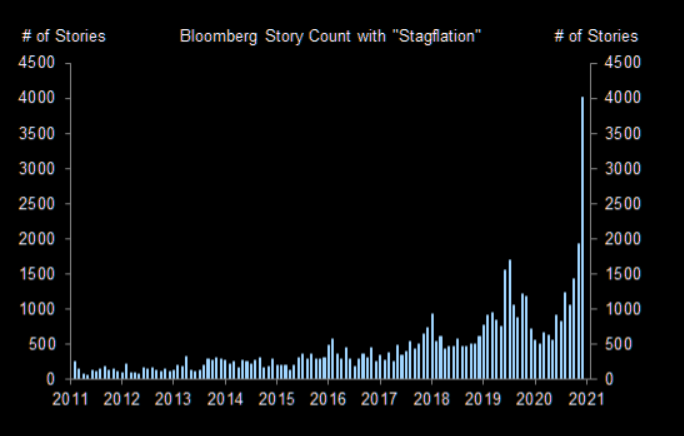

Stagflation

Combine stubbornly rising prices and rapidly slowing growth in the world’s two largest economies and the subject of stagflation suddenly begins to take hold. The emergence of stagflation as a scenario to be considered is depicted in the graph from themarketear.com ($, Oct 10, 2021).

Transitional transitory

While the Fed’s line has been for only “transitory” inflation, new indications of inflationary conditions keep popping up and something more seems to be at work. Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic this week characterized the price increases resulting from supply chain disruptions as likely to last, implying they are not transitory. The CPI for September also came in warm at 5.4% and at 4.0% on a core basis. In that number, owner’s equivalent rent (OER) jumped to 0.4% month over month indicating higher home prices are beginning to filter through into inflation.

In addition, the ability of supply to adjust to demand conditions is being constrained by more than just supply chains. As Jason Bordoff intimates, energy production is being constrained by public policy. The challenge is even worse than that, however, as activist investors are pressuring Exxon Mobil and Chevron to reduce investment in oil fields. If supply cannot respond to demand by way of price signals, words such as “difficult”, “disruptive”, “messy”, and “super volatile” are absolutely appropriate for describing the energy transition.

Not to be left out, the labor market is also showing signs of transitioning awkwardly from transitory issues to more persistent ones. What we know is voluntary quit rates are up. The Washington Post reported:

“Some 4.3 million people quit jobs in August — about 2.9 percent of the workforce, according to new data released Tuesday from the Labor Department. Those numbers are up from the previous record, set in April, of about 4 million people quitting, reflecting how the pandemic has continued to jolt workers’ mind-set about their jobs and their lives.”

Southwest canceled 1900 flights over the weekend and hundreds more early in the week in what does not appear to be an exclusively weather-related incident. Is this an aberration or the beginning of a troublesome trend? We’ll have to wait and see, but signs point to more takes on the sickout theme.

Jeremy Rudd tackles yet another issue in his recent paper on inflation expectations:

“Likewise, the survey evidence on why people dislike inflation reported in Shiller (1997) indicates that a major concern is that their wages won’t keep up with price increases—which certainly doesn’t suggest that they view themselves as having much bargaining power with their existing employer.”

Other paths

While there are several indications of pricing pressure across various dimensions, there is also evidence deflation may be the bigger threat. Rising commodity prices have stoked recent concerns about inflation, but Gary Shilling outlines eight reasons why the rally in commodities is likely to end soon in his latest newsletter. Slower growth globally, and in China are the top two reasons. Excess supply and the strength of the US dollar also contribute. All the ideas are sound.

In addition, while longer-term interest rates have been trending up since early August, they have reversed the last few days. This flattening of the yield curve, while still very preliminary, presents troubling evidence for the inflation case.

Implications

So, where does this leave investors? The most obvious conclusion is the environment is becoming considerably more muddled than “The Fed has our back”. As a result, the prescription must be more nuanced than “Buy the dip”. As The Market Ear described on Oct. 13, “The aggregate psychology of this market is very complex and interesting right now.”

Investors who have profited by riding the wave of ever higher stock prices should probably read “complex” and “interesting” as “harder”. One of the most powerful tailwinds for both stocks and bonds has been declining interest rates. If rates continue rising, or can plausibly be considered to continue rising, much of the old playbook is going to have to be reconsidered.

For one, protection, or at least risk management will have a valuable role to play again. At the Global Independent Research Conference on Wednesday, Jim Grant explained “the muscle memory of four decades of declining rates conditioned people to expect anything but inflation”. As a result, he thinks people have become conditioned to “disregard the usefulness of margin of safety”. So, it’s a good time to bone up on margin of safety or to take a refresher course.

Along the same lines, Dylan Grice (on the same panel at the conference) warned “all roads lead to duration.” In other words, the phenomenon of declining interest rates has been an enormous tailwind for a vast array of investment strategies. Given the many miscues on inflation the last several years, he suggested “we should have learned some humility.”

His investment answer is to avoid taking a big bet on the inherently uncertain prospect of inflation altogether. More specifically, he prefers to “sit on the fence” and avoid taking the big duration bets inherent to owning stocks and bonds. His point is, “it is easier to find duration-free investments than picking the direction of rates.”

Conclusion

Since early September, the S&P 500 has looked uncharacteristically lethargic. Even with a big pop on Thursday (10/14/21), it is hard to deny the landscape is becoming more “complex”.

A big part of the problem has been the persistence of inflationary forces. While it may be tempting to determine the most likely direction of price pressures and to make a bet, some of the smartest people in the room are advocating for humility on the subject. Indeed, the avoidance of purely directional plays and the implementation of risk management are pages from a very different playbook.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed