November 2015

Investors have been captivated by the ongoing saga of extraordinary monetary policy as if it were a real life soap opera. Following spectacular plot twists and improbable events, the drama has left investors breathless and the story line ... to be continued.

But as low rates have persisted, what used to seem like a bizarre, but temporary, condition now seems routine. As a result, it is fair to ask: What would happen if zero, or even negative, rates were to be continued indefinitely? In that extreme case, investors would find themselves in a very different world and in the words of Rod Serling, "traveling through another dimension". Are investors entering ... The Twighlight Zone (cue The Twighlight Zone theme music [here])?

To be sure, the odds of a rate hike in December are fairly high right now. That said, most economic data continues to come in on the weak side which will make it harder for the Fed to actually pull the trigger and raise rates. Remember, odds were also good for a September rate hike but that prospect quickly diminished as emerging market turmoil arose at the end of the summer. Further, a single rate hike of a quarter point still would not get us anywhere near what could be considered "normal" rates. Several more rate hikes would have to follow and if any trouble arises during that journey, there is a good chance the Fed would either stop raising rates or even reverse course.

As a result, it makes sense to consider the prospect that rates don't normalize. In the event that low rates become a permanent fixture, some important things will change. For one, we know that people respond to permanent conditions differently than to temporary ones. This reality is also firmly rooted in economic theory. The "permanent income hypothesis", for example, describes that a person's consumption patterns are affected "not just by their current income but also by their expected income in future years" [here].

In short, the theory states that "changes in permanent income, rather than changes in temporary income, are what drive the changes in a consumer's consumption patterns." From this we can infer that as the perception of lower income accruing from investments (due to low rates) transitions from being a temporary condition to being a permanent one, consumer consumption patterns are also likely to adapt.

The possibility of a "permanent" condition of low rates would fundamentally change other aspects of the investment landscape as well, the consequences of which Bill Gross highlighted in his latest letter [here]. After suggesting that the "historical conceptual models" that are used by the Fed may actually be "hazardous to an economy’s health," he went on to describe why. In his mind, "capitalism does not function well, and profit growth is stunted, if short term and long term yields near the zero bound are low and the yield curve inappropriately flat." He summarized, "investors would have no incentive to invest long term." Not surprisingly, this would severely impair a lot of existing business models.

Skepticism of the benefits of low rates extended long term is also shared by some policy makers. Charles Gave reports [here]: "If rates were held too low for too long, warned Rajan, the risk of financial instability would be greatly heightened, a concern Weidmann said he shared." This prognosis carries extra weight coming from Raghuram Rajan and Jens Weidmann who are both giants of the central banking community.

In addition to magnifying the risk of "financial instability", the extension of low rates for longer also harms anyone trying to plan for the future. That includes anyone trying to be responsible, to live within their means, and to save. Indeed it is exactly the notion that time and uncertainty create risks which need to be compensated that forms the foundation of a capitalist economic system. When those principles break down, it will undermine the economic foundations of entire industries. Gave points out two of the most visible ones: "By far the biggest pools of savings today are the pension funds and the life insurance industry."

The case against pensions is especially clear as highlighted in the latest update of pension disclosures by SEI [here]. It reports, "Of the 679 plan sponsors reporting ROA (return on assets) assumptions, most (68%) had ROAs between 7.00% and 8.25%." Just taking the midpoint of that range, 7.62%, we can see that some pretty hefty returns will be required to keep these pensions afloat.

Unfortunately, the prospect of hefty returns looks to be a long shot. As The Economist reports [here], Elroy Dimson, a professor at both the Cambridge and London Business Schools thinks "the likely future long-term real return on a balanced portfolio of equities and bonds will be 2-2.5%." These returns, the natural consequence of a world with low rates and high stock valuations, will not be enough to keep the payouts promised by many pension funds. But then they won't be enough to keep the promises of many insurance companies or the assurances of comfortable retirement by many financial advisers either. In a world of permanently low rates, the economic fallout will be widespread.

The implications of "low rates for longer" also extend beyond just the economic, however, and reach deeply into the political. Gave describes that "cutting interest rates should lead to a higher level of economic activity today, to be paid for by a lower level of activity at some point in the future.” As a result, the policy of low rates for longer comes at the expense of future generations by depriving them of their fair share of economic activity. By depressing returns, the policy also substantially reduces the ability of younger generations to reap the due rewards of investing in financial assets in order to create a more secure future.

In summary, economic theory is all about incentives. It follows that a world in which public policy (in the form of monetary policy) that creates perverse and counterproductive incentives is indeed a strange one. The notion that such a policy might be continued indefinitely is stranger yet, though one that investors need to consider. As Bill Gross wrote, "central bankers are not dumb, but they are stubborn,"

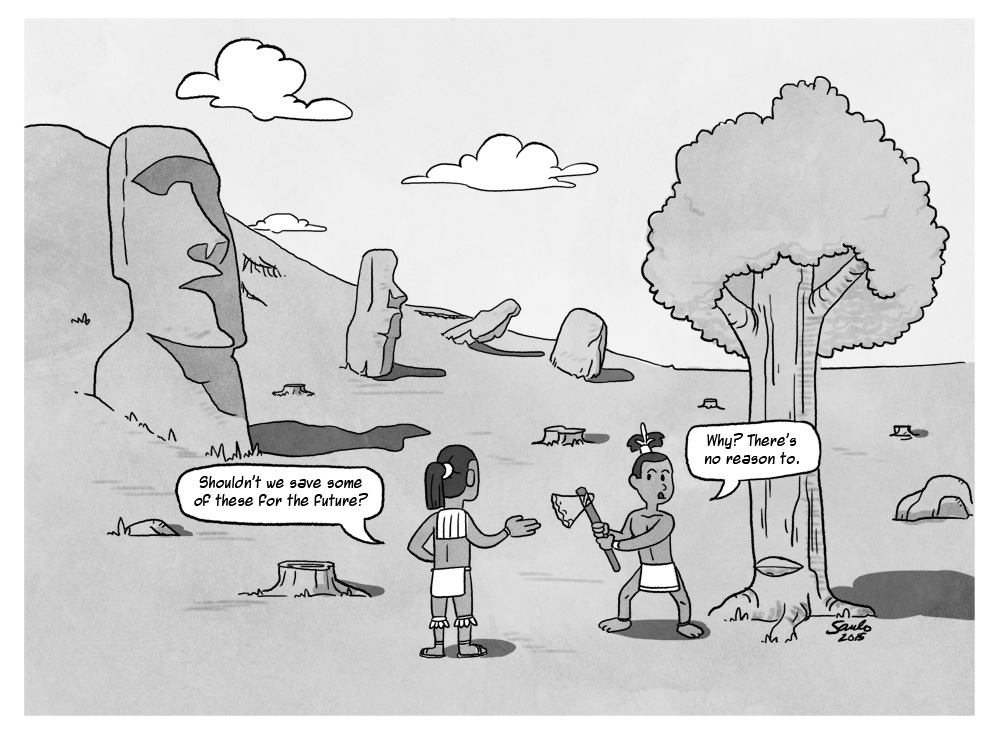

What if the Fed drama does continue indefinitely? What should investors do when there is a dangerous scarcity of good long term investment opportunities? What should investors do to avoid a disaster like Easter Island which is an all-too non-fictional example of consuming too much in the near term at the expense of appropriate investment in the long term?

The first route many have taken is to pursue investments that are riskier and/or more illiquid such as hedge funds, private equity, venture capital and the like. This is harder for retail investors to do than for institutions and regardless, it is usually much more costly (for both types of investors) in terms of management fees. This course may help a bit on the margin, but it is unlikely to completely overcome low returns due to a large number of practical constraints.

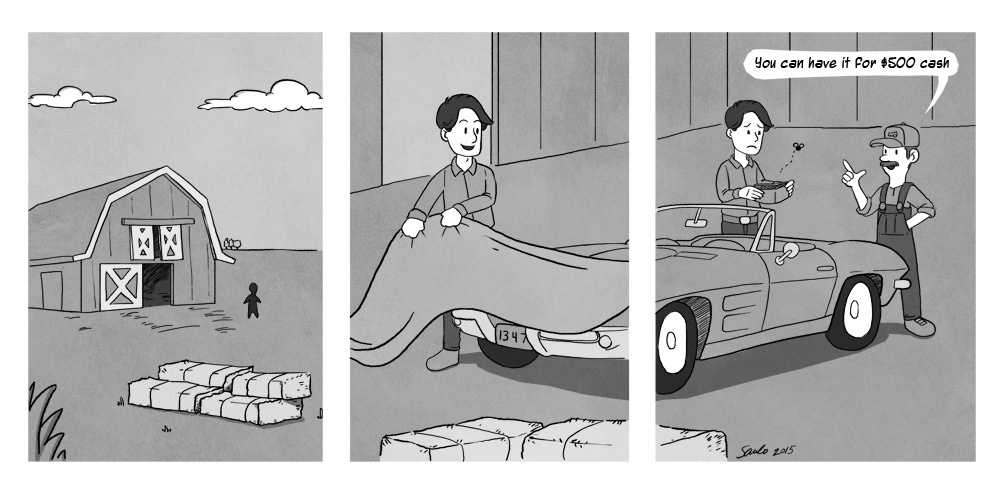

It probably makes sense to have some cash available almost regardless of what your view of the future is, as we also noted in our last post [here]. The downside of taking this position too far is that you are playing a waiting game - and you could be waiting a long time. That said, in the absence of better alternatives cash may still be appropriate, especially for incremental inflows such as year-end bonuses and holiday money. You don't get paid for holding it, but you don't risk much either.

Perhaps most interestingly, one option for contending with an extended period of low rates is to broaden one's perspective of investing. In a general sense, investing is an activity in which one defers gratification for a greater benefit later. While investing normally applies to financial assets such as stocks and bonds, it can absolutely apply to oneself in the form of education and training.

For example, if you get a degree or a professional certification, it often leads to a permanently higher future stream of income (through a better job, promotion, side jobs, etc.) that more than offsets the cost. Of course cost is an important factor and a number of university programs are expensive. There are, however, an ever-expanding number of cheap and free classes online. For those who prefer to learn on their own, most ebooks are cheaper than hardcopy books and municipal libraries still provide a great and free resource! Even short courses on writing, software coding, website development, etc. can open up new sources of revenue. As opposed to financial assets, the prices of many educational investments have gone down and are extremely attractive.

While investing in education and training does not generate the same kind of effortless returns as investing in financial assets, neither is it nearly as affected by monetary policy. This means that people who invest in themselves tend to have much more control over the outcome than they do when investing in financial assets. Further, when the expected returns on financial assets are very low like they are today, then there are exceptionally low opportunity costs as well.

As low rates keep getting pushed out for longer, investors increasingly have to consider the possibility of permanently low rates and it behooves them to consider the implications. The lesson from the history of Easter Island is that an extended period of consuming too much in the near term at the expense of long term investments can cause irreparable damage and long term decline. The bottom line is that such a world would be very ugly for many of today's businesses, but it doesn't have to be for investors. There are still reasonable courses of action investors can take to invest in their future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed