March 2017

Once upon a time, analysts determined a company's value by discounting its cash flows and economists evaluated growth potential by assessing population growth and productivity.

While those activities are still absolutely relevant, they have increasingly been overshadowed by the effects of a secular expansion of credit. Just like riding a bike with the wind at your back can make you feel like a pretty strong cyclist for the time, so too does increasing debt provide a tailwind that flatters economic performance. In light of these alluring benefits, what can hold back the further acceleration of debt?

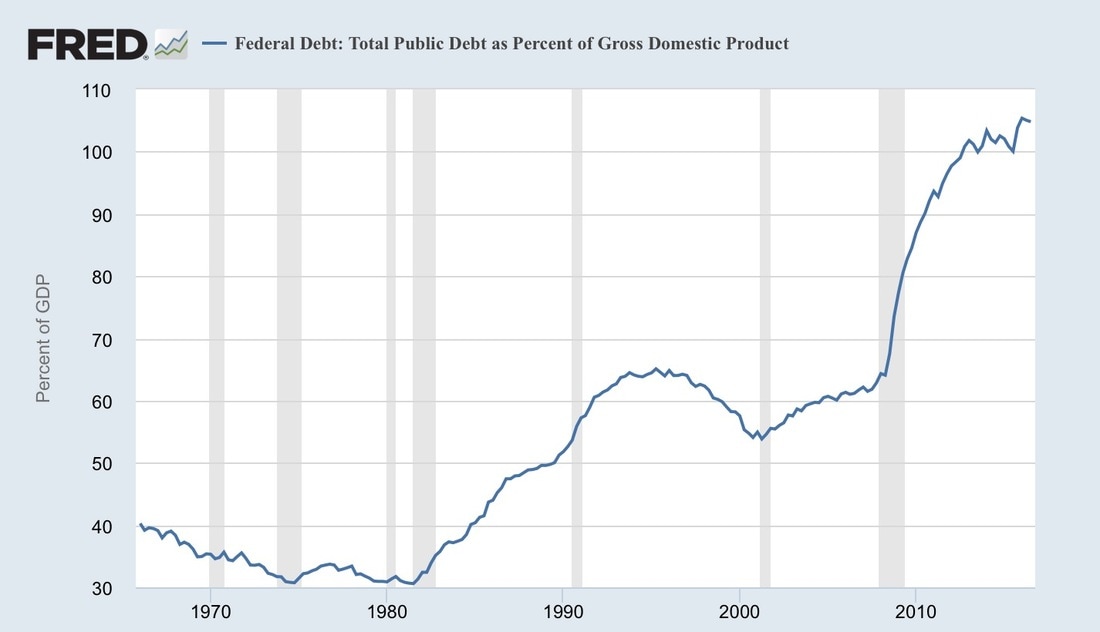

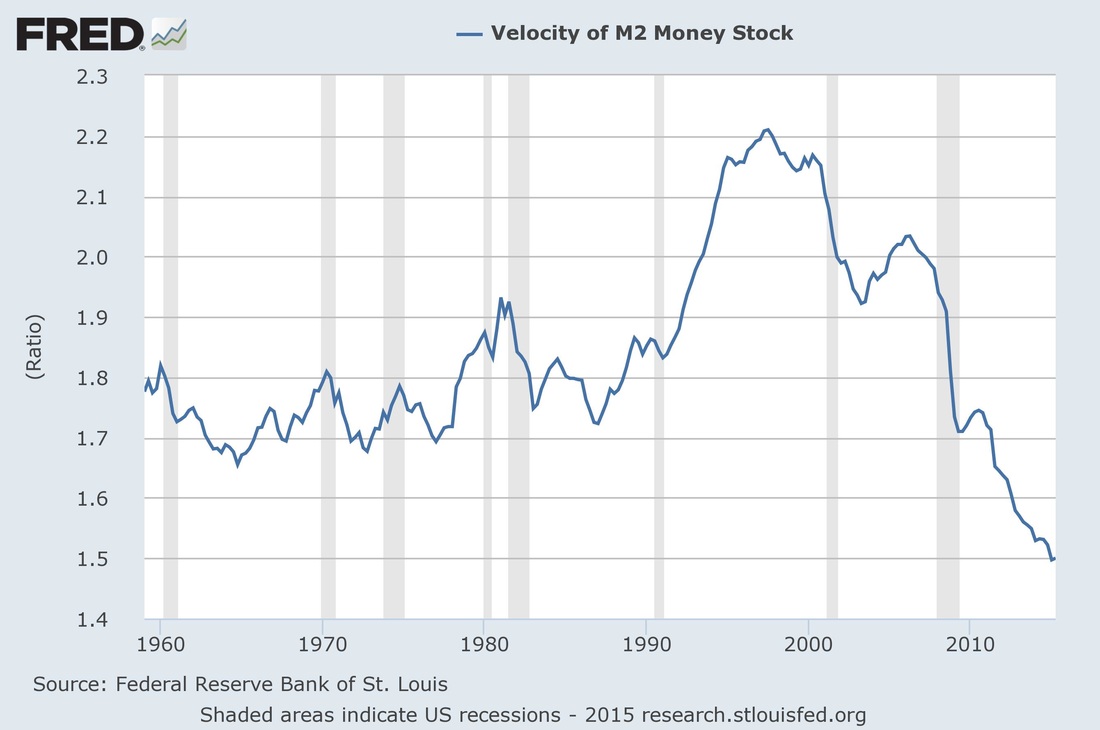

The chart below (which is easily accessible from the St. Louis Fed website [here]) tells the important story of how growth in debt has outpaced that of GDP by a large margin in the US over the last fifty years. While debt declined in relation to GDP through the early 1980s, it rose sharply through the mid 1990s and then sharply again from the financial crisis in 2008 until today.

When the repercussions of this activity were revealed in the financial crisis, some emergency measures were required to help prevent a complete melt-down in the financial system. Reasonable requirements for recapitalizing banks, for example, helped to build a better foundation for the system of credit. There was even optimistic talk of a "beautiful deleveraging" in which the economy would gradually and smoothly adjust to lower and more stable levels of debt.

Alas, it quickly became obvious that no lasting lessons were learned. Deleveraging was a nice narrative, but only a narrative. The only substantive public policy response to the crisis came from central banks and they tried to manage unwieldy debt levels by keeping interest rates artificially low. Not surprisingly, low rates encouraged additional borrowing, the very heart of the original problem. The feeble public policy response prompted Klarman to complain, "The imagination of our financial leaders remains so shallow that their response to a crisis caused by overleverage and excess has been to recreate, as nearly as possible, the conditions that fomented it, as if the events of 2008 were a rogue wave of financial woe that can never recur."

Indeed, businesses, households, and government all responded to exceptionally low rates by quickly reverting to their borrowing binge and "recreating the conditions that fomented the financial crisis". Growth in household debt, business debt, and government debt all outpaced GDP growth over the last five years.

This seemingly mindless loop of credit-fueled growth is captured all too well by the old phrase, "Lather, rinse, repeat". Wikipedia describes the phrase [here] as "a sarcastic metaphor for following instructions or procedures slavishly without critical thought." It also points to the logical conclusion of following such a pattern: "Such instructions if taken literally would result in an endless loop of repeating the same steps, at least until one runs out of shampoo."

One could replace the word "shampoo" with "credit" and have a reasonably accurate depiction of the process of credit formation. Given the nearly insatiable demand for credit, which prompts economic participants to borrow "slavishly without critical thought", what might cause them to eventually "run out of credit?" What could halt the process?

Jim Grant addresses this very point in the February 10 Interest Rate Observer: "What might stymie the early restoration of red-blooded credit formation? Pure and simple, credit already incurred; Note, for example, the slow-down in the growth in business lending and M-2 alike [annualized rates of growth in commercial and industrial loans slowed from 7.3% 12 months ago to 3.7% 6 months ago to 3.0% 3 months ago and commercial bank credit slowed from 6.6% 12 months ago to 5.4% 6 months ago to 3.0% 3 months ago] ... Or peruse the Federal Reserve's January Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey. In it, banks reported a dip in demand for residential mortgages and construction loans."

This assessment is also corroborated in the market for small business loans, despite positive sentiments expressed since the election. The Financial Times reports [here], "'January was slow, February is slower,' said Rohit Arora, co-founder of Biz2Credit, which arranges loans for small companies. ‘Political uncertainty has gone up so much since Trump came in’." David Rosenberg, the respected chief economist at Gluskin Sheff, noted, "The recent lending data had 'sent a shiver up my spine.' Lending had 'fallen off a cliff' he added."

In addition, car loans are beginning to show weakness as well. Grants reports in the February 24 letter: "The banged-up state of auto finance is topic No. 1. National loan delinquencies, prime and subprime alike, rose by 13% year over year in the fourth quarter, to 1.44% of all loans outstanding. It was the highest level of slow payments since the fourth quarter of 2009, according to credit bureau TransUnion. The deterioration in credit came despite a 2.2 million lift in 2016 non-farm payrolls and a year-end unemployment rate of 4.7%, down from 5% at year-end 2015." The FT adds [here], that, "More than a million US consumers have fallen at least two months behind on car loan repayments."

Grants describes the rapid restarting of the credit machine since the financial crisis: "Emboldened, lenders shed bust-era inhibitions. By 2016, 31% of loans financing new-vehicle sales involved negative equity from a trade-in; up from 25.6% in 2013." It's not hard to imagine negative equity on trade-ins when, as the FT reports, "The average borrower has about $18,400 in debt on their car loan — up about a tenth from three years ago."

Further, in a flashback from the housing crisis, the fastest growth has been among the poorest credits. The FT describes, "Lending to consumers with weak credit scores has been one of the fastest-growing parts of the industry." This factoid is especially troubling given that auto lending was the one area that held up reasonably well through the housing crisis.

At the same time that growth in credit is being constrained by demand, it is also being constrained by supply. Highlighting an issue that rarely makes headlines, Grants reports, "'The guy that can't get financing is the guy who has a new idea, who has some net worth—but not a lot of net worth, the numbers look OK—but you wouldn't make the loan just on the numbers,' John Allison, former president and CEO of BB&T Corp told Grants ... That market's been closed down'." In other words, credit is being tightened in exactly the places that can provide sustainable growth.

In light of debt burdens that are clearly beginning to weigh heavily again, it is not surprising to hear that some borrowers are adapting unconventional responses. For example, zerohedge reports [here], "According to a survey of 500 current college students conducted by LendEDU, apparently 49.8% of America's entitled youth is convinced that the federal government will simply forgive their student loans upon graduation...call it a nice little taxpayer funded graduation gift."

The mindset of treating debts as something less than strictly binding recalls the practice of "jingle mail" during the housing crisis. This occurred when falling home prices caused homeowners to fall into a negative equity position so onerous that they deemed it more beneficial to just walk away from the house and the mortgage. This "strategic default" freed up their income to be spent on other things.

In both cases, what counts as someone's liability counts as someone else's asset. When people borrow without the full intent of paying a loan off, that loan becomes less valuable as an asset. The situation begs the question, "How many car buyers feel the same way? How many credit card holders?" Regardless, some investors will be disappointed.

As if there aren't already enough problematic indicators for credit, David Stockman highlights yet another one in zerohedge [here]. Stockman notes, "I think what people are missing is this date, March 15th 2017. That’s the day that this debt ceiling holiday that Obama and Boehner put together right before the last election in October of 2015. That holiday expires. The debt ceiling will freeze in at $20 trillion. It will then be law. It will be a hard stop. The Treasury will have roughly $200 billion in cash. We are burning cash at a $75 billion a month rate. By summer, they will be out of cash. Then we will be in the mother of all debt ceiling crises. Everything will grind to a halt. I think we will have a government shutdown."

What does all of this mean? First and foremost, there are limits as to how much debt can increase and we may well be breaching those limits. In the short term, debt payments can become unwieldy even at incredibly low interest rates, as the rising delinquencies of car loans and a host of other indicators suggests is currently happening.

In the longer term, the sustainability of debt is partly a function of politics. Since debt pulls demand forward, it shifts benefits from one period of time to another. When this happens over longer periods of time, entire generations can be affected. Someone must bear those burdens and too often they fall on younger generations who cannot yet vote in the matter or do not have sufficient political power to change course. Such inequities have social and political consequences that very much affect the planning horizons of long term investors.

Another major takeaway is that economic growth prospects can only be accurately assessed in the context of credit conditions. While this may sound somewhat obvious, it can be deceptively easy for investors to focus too narrowly and miss the broader perspective.

As an interesting example, David Eagleman recently wrote in the FT [here] about his research in neuroscience to reduce counterfeiting. It turns out that counterfeiting often works because when people are engaged in ordinary activities they often don't notice when something is amiss. As Eagleman describes, "So our visual sense is not like a camera that takes in the complete scene. Instead, we see only the details that our brains go out to seek." In other words, "We don't attend to things that sufficiently fit our assumptions. We believe we already know the note in our hands."

The same neuroscience also applies to investment analysis. Too often, "we believe we already know the economy" and do not seek out the relevant details about debt and credit. One risk in doing so is to overestimate economic growth potential. When growth has been boosted by a secular increase in debt, as it has, impending limits on debt will also constrain the potential for economic growth. In addition, overlooking debt and credit carries the risk of missing the fairly reliable warning signals that are sent by slow-downs in credit.

Another risk of overlooking the effects of credit on economic growth is to miss its procyclical nature. Because credit overshoots in both directions, it tends to breed instability and compound problems (a point we noted previously [here]). One of the many problems with increasing credit availability, either by easing terms or suppressing interest rates, is that it provides an important incentive to increase, not decrease, leverage. These incentives foster fragility in the financial system and make it easier to break.

Importantly for investors, a policy response to high levels of debt that favors monetary easing over deleveraging also creates perverse incentives. In an environment of persistent central bank support, "bad news" on the economic front has signaled "good news" in the form of continued intervention and support for market prices. The result has been to teach all the wrong lessons for long term investing. When central bank support falls away, bad news will again be treated as bad news and many of the lessons learned over the last eight years will become significantly counterproductive.

Finally, it is always a challenge to assess market risks and opportunities. It is easy to get caught up in market frenzy, second guess evidence, let one's imagination fly and ultimately oversimplify and misdiagnose underlying market conditions. One thing that can help investors stay on course during their journey is to maintain a conceptual "true north" by which to gauge long term risks and opportunities. Credit metrics provide an extremely useful complement for investors in stocks to help anchor and calibrate fundamental analyses.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed