February 2016

Football is a great deal like life in that it teaches that work, sacrifice, perseverance, competitive drive, selflessness and respect for authority is the price that each and every one of us must pay to achieve any goal that is worthwhile.

- Vince Lombardi

As we approach Super Bowl Sunday, it is easy to appreciate all of the energy and hard work that goes into reaching the final stage of the NFL championship. Not only does the game represent the pinnacle of achievement in one of America's favorite sports, but it also engenders many of the qualities Lombardi mentioned such as sacrifice, perseverance, and selflessness.

Given the country's affection for the game and the qualities required to compete at such a high level, it is astonishing that so few of these qualities are brought to bear on a much bigger real life challenge: managing the liabilities of health care entitlements such as Medicare and Medicaid. In this important respect, football isn't so much like life, as Lombardi proclaimed, but rather may serve as a useful guide for confronting one of its most difficult challenges. What might the great coach (or any great coach for that matter) say about taking on entitlements, and how is it relevant for investors?

Most fundamentally, it makes sense to determine if the goal of dealing with entitlements is even one that is worth pursuing. Realistically, few people have little more than a vague notion of what kind of challenge healthcare liabilities present. The ambiguous perception of the challenge tends to attenuate any impetus for change.

Decent estimates for entitlement liabilities are not widely discussed but can be found. Part of the reason they avoid greater scrutiny is because they are not addressed directly as a form of debt; rather they are essentially off balance sheet liabilities. Nonetheless, Mary Meeker's presentation entitled, "USA, Inc." [here] given at the Ira Sohn conference in 2012 provides a very credible context and source of data. According to Meeker, the present value of unfunded Medicare liabilities amount to $22.8 trillion and underfunded future Medicaid expenditures amount to $35.3 trillion.

Granted, it is hard to fully appreciate what these numbers mean given how mind-bogglingly large they are. In order to better appreciate their magnitude we can scale them to the number of households. The total liabilities of $58.1 trillion (22.8 + 35.3) divided by the number of households (123.2 million in 2014) = healthcare entitlement liabilities of $471,590 per household.

In some form or another, this is the burden that is hanging over every household in the US. Other comparisons are no more flattering. Compared to median household income of $51,939 (2014), the entitlement liability is just over nine times. This compares to the rule of thumb that households can afford to buy a house that is two to three times their gross income. The entitlement liability is at least three times bigger yet.

There are two simple conclusions from this analysis. One is that yes, dealing with entitlements is a goal that is worthwhile. Not only is this a big game, it is the big game. The liabilities are so large that they present a nearly existential risk. They are not literally an existential threat to our beings, but they are certainly an existential threat to any preconceived notions of financial security and quality of life. Every successful coach knows that it's important to respect the opponent and entitlements represent a formidable opponent.

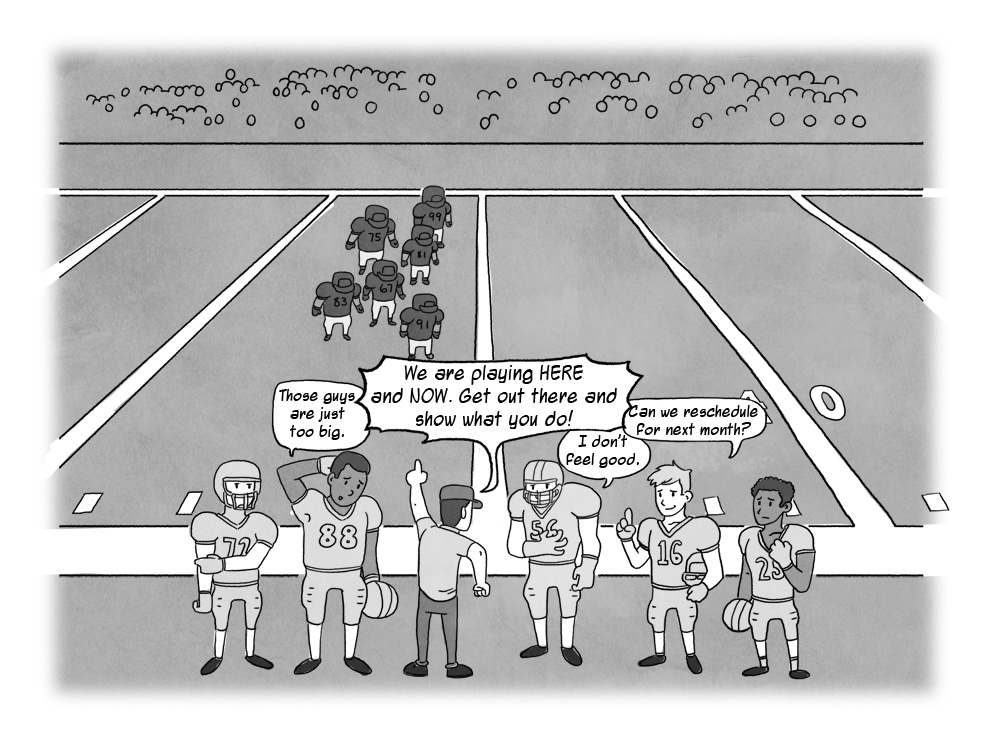

This leads to another simple conclusion: we are all players in this game. One way or another we will all be affected. Individuals who believe that these issues won't affect them or just want to sit the game out do not (yet) understand that the game will come to them. They are involved whether they want to be or not.

Given this reality, any good coach would emphasize that first and foremost we are all on the same team. As Lombardi noted, "selflessness" and "sacrifice" are going to be required in order to achieve our goal of managing entitlements. This stands in deep contrast to the partisan polarization we find in today's political climate. Yes, there are different views about how to make tradeoffs. But there cannot be any doubt that we will all need to make sacrifices and to exercise selflessness nor that healthy debate will be far more constructive than squabbling.

A good coach also knows that when winning matters, it is critical to have an honest assessment of your own strengths and weaknesses and how they match up with the opponent. In this regard, the study “Persistent Overoptimism About Economic Growth” by Kevin J. Lansing and Benjamin Pyle and published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco [here] makes the economics team (as represented by Fed economists) look like a group of amateurs. Lansing and Pyle conclude that, "Since 2007, Federal Open Market Committee participants have been persistently too optimistic about future U.S. economic growth. Real GDP growth forecasts have typically started high, but then are revised down over time as the incoming data continue to disappoint."

Persistently overoptimism is a fine quality for cheerleaders hoping to boost morale for a time, but is counterproductive for a team trying to win a game. Lansing and Pyle offer their own hypotheses as to why the Fed (and plenty of other economists) have been systematically off the mark: "Possible explanations for this pattern include missed warning signals about the buildup of imbalances before the crisis, overestimation of the efficacy of monetary policy following a balance-sheet recession, and the natural tendency of forecasters to extrapolate from recent data." In other words, just about everything has gone wrong from misdiagnosing the problem, to applying economic models that don't work to failing to be objective by allowing bias to affect decision making. The coach can't possible be happy about that performance.

A good coach also needs to be able to adjust the game plan as necessary and this has also been a weakness. If a team keeps running the ball up the middle and keep getting stuffed it isn't going to make any progress. And yet this is almost exactly what is happening with economic policy. Time after time the Fed tries new extraordinary measures of monetary policy to contend with weak growth and time after time it fails to accomplish anything meaningful. A good coach can adjust to conditions and make mid-course corrections if the original plan isn't working.

Given the formidable opponent that healthcare liabilities present, they will have to be dealt with one way or another and Michael Pettis provides a useful framework from which to assess potential outcomes. Although he writes about Chinese debt specifically in his blog post, "Will China's new 'supply-side' reforms help China?", he uses the same broadly applicable analysis that he does in his book, Volatility Machine.

Notably, he describes unsustainable debt burdens (which healthcare entitlement obligations effectively are) "are always resolved by mechanisms in which debt-servicing costs are explicitly or implicitly allocated to some sector of the economy, usually unwillingly." As a result, even though we face some very difficult decisions on how servicing costs get allocated, at least early action will be rewarded with having some choice in the matter.

Pettis also does a nice job of framing the possibilities for allocating costs. He describes that, "Repaying debt simply means allocating debt-servicing costs, either directly or indirectly, to specific sectors within the economy. This will either occur in ways targeted by policymakers, or if postponed for too long, it will occur in unpredictable ways determined by circumstances. For example, default allocates the costs to creditors, inflation allocates the costs to household savers, economic collapse and high unemployment allocates the costs to workers, etc."

It is not hard to extend this logic to unsustainable entitlement commitments. The costs can be allocated to beneficiaries (though reduced benefits), to household savers (though inflation), and to workers (though economic collapse). It's also not hard to see that each group is interdependent and that we really are all in this together. How can any combination of health benefit cuts to retirees, household saver purchasing power weakening due to inflation, and weak economic growth depriving workers of jobs not hurt all of us?

The situation is an accident waiting to happen, as can be seen by the chart in Meeker's "USA, Inc." presentation on slide 38 [here]. On one hand, entitlement spending will continue to increase as more and more baby boomers retire. At the same time, the ratio of workers/retirees will be declining which will continue to impede the growth of tax revenue over time. Things aren't going to get easier. We might be inclined to watch the situation unfold with some morbid curiosity if we weren't sitting in the middle of the back seat and at risk of flying through the windshield when the accident happens.

Tough challenges arise all the time. One quality that really differentiates pros from amateurs, however, is that pros never give up. That is partly why so many football games are decided in the final seconds; it is an intense competition. Sure, sometimes it seems like everything that could go wrong does go wrong. Sometimes a team is just outmatched. Pros still show up and do the best they can whereas amateurs often give up, completely demoralized.

In conclusion, this contest with healthcare entitlements is a big one and has significant implications for investors. For example, because the liabilities are so big, there are quite likely to be major redistributions of wealth. It is also quite likely that each of the scenarios Pettis mentions will come to pass in varying degrees. The numbers are too big for the pain not to be shared. This means we are all going to be affected so we are all in this together. It also means that planning for financial security in the future will be nothing like it has been in the past, not least of which is because none of us has the amount of wealth that we think we do.

When push comes to shove, the government is going to be searching far and wide for any monies that can help pay for entitlement commitments. Taxes, in many different forms, are quite likely to go up and even more likely for high earners. It will call for measures that will be shocking for many in their nature and scope. Retirees will need to anticipate the potential for significant reductions in entitlement benefits exacerbated by increasing taxes in order to avoid depleting their retirement savings early. Younger adults will need to continue adapting to a lower cost lifestyle while also maintaining resilience to economic and financial shocks by constantly updating and upgrading their skillsets.

So we can either make difficult choices in regards to entitlements, or those choices will "occur in unpredictable ways determined by circumstances". It will be harder than in the past, but the past is a false comparison. We played an awful first half and have a lot of catching up to do.

Vince Lombardi once said, “To achieve success, whatever the job we have, we must pay a price.” In regards to entitlement spending, it is clear that we must pay a price, but at this point, we aren't even discussing a strategy. Competitors hate to lose, but it doesn't even seem like we are trying to win this one.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed