October 2014

For the last four years the market has continued an almost uninterrupted rise with seemingly little concern for risks, including extended valuations. The rebound that began in 2009 did originally have clear valuation support, but that quickly eroded and has been long forgotten. Now market action is considerably more unsettled and investors are left debating whether recent turmoil is an unpleasant, but brief, intermission or the end of a long run. While we hesitate to make any specific predictions due to the inherent complexity and uncertainty of markets, it certainly seems like something has changed.

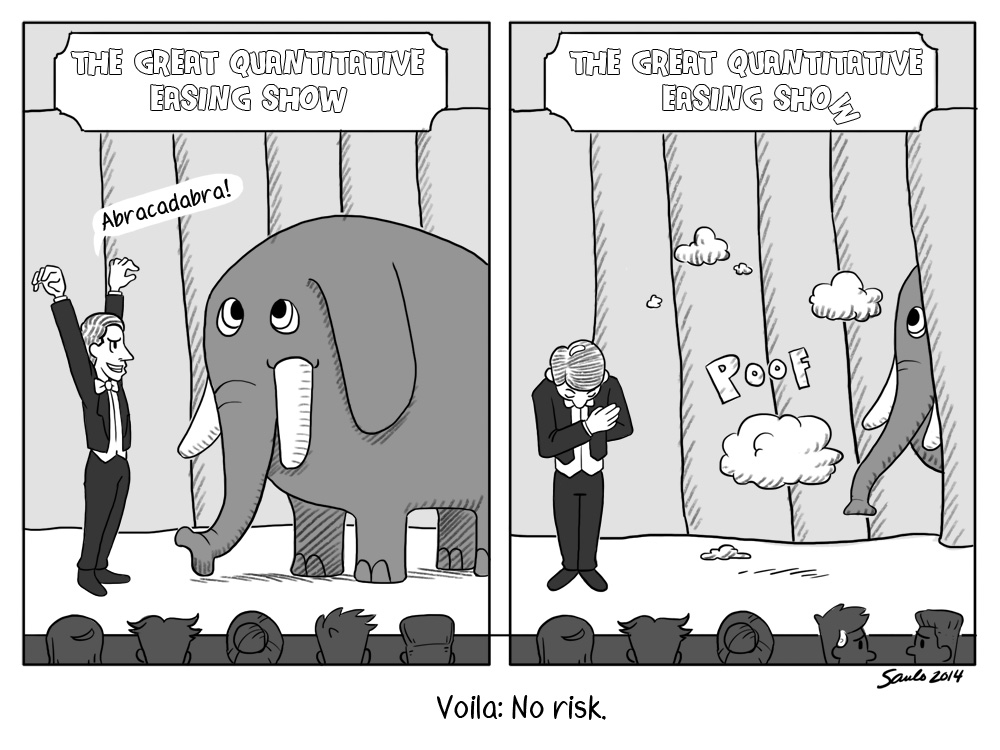

That "something" is the imminent conclusion of the Fed's program of quantitative easing (QE) -- and the many ramifications of its continued deployment. The mechanics of QE are such that the program artificially depresses interest rates and therefore artificially inflates virtually all asset prices. In doing so, it provides a nice little "wind at the back" of the market for a period of time, but not on any sustainable basis.

What QE also does, however, is to make it dangerously easy to miss the elephant in the room. Risk can still be found in the forms of high valuations, weak and structurally flawed global economic growth, extremely high debt levels, geopolitical conflicts, and public policy that has almost completely failed to meaningfully address any of the critically important issues emanating from the crisis of 2008-9.

It has almost been like the Fed's big magic trick: drop the screen over risk (in its many forms), wave your magic wand by implementing QE, raise the screen and abracadabra: risk disappears -- nobody sees it any more. Just like in real magic tricks, though, risk didn't actually disappear, investors just didn’t see it. Now that the QE show has nearly concluded and the audience is starting to leave, lo and behold, the elephant is still there! While the central banker magicians have put on a credible act, investors' willingness to suspend disbelief in the illusion has contributed meaningfully to its success.

An unfortunate consequence of being entranced by this "magic" show the last four years is that investors have become acclimated to a world without elephants. Out of immediate sight, out of mind. As investors reacquaint themselves with the real world that does have risk in it, several adjustments will have to be made. For example, one of the important consequences of QE is that is has allowed large companies to borrow cheaply and use the proceeds to repurchase shares. The repurchase of shares has been on such a large scale as to constitute a very significant marginal buyer in the market. Given the typically procyclical nature of share repurchases, once this tide turns, a great deal of buying pressure will dry up and we already started seeing this in the second quarter.

Another adjustment will be required to incorporate the reality of weak economic growth. While there are different causes and contributing factors for this in different parts of the world, in the U.S. demographics is going to create a noticeable headwind in the near future. Demographic patterns (Harry Dent, The Demographic Cliff) tell us that in households spend the most when the head is 46 years old. More affluent households (those who were least affected by the financial crisis of 2008-9) peak in spending between the ages of 51 and 53. As it turns out, demographic data also reveal that the single largest age cohort in the Baby Boom is 53 this year (and was 46 in 2007). This suggests that for the next several years, we can expect a precipitous drop in overall consumer spending as Baby Boomers roll out of their peak spending years and start saving more. While this won't be the end of the world by any stretch, it will provide a substantial, and largely underappreciated headwind for the next several years.

There are several signs that this adjustment process is starting in the first days of the fourth quarter. Volatility has increased markedly, market internals have weakened, and most major indexes are down. Interestingly, this episode differs from similar ones over the summer and after the "taper tantrum" last summer. For example, this period of instability is lasting longer and volatility measures are much more elevated. In addition, in the past when the market would swoon for a couple of days, leadership within the markets did not change materially but now it has. In the past, efforts to revive momentum succeeded fairly quickly; now they are short-lived and quickly reversed. Value has also been performing better and when the market rebounds off of bad days, it is far rarer for the big momentum stocks to be the ones leading the charge back.

Is it possible that this is just another intermission in the show and that central banks could try to keep markets afloat a bit longer? Sure, it's possible, but there is still useful information content in recent market activity. For one, without clear direction on the future of QE, it is far harder for traders to make a one way bet on the market. As such, there is not only one less source of buying pressure, but there is also quite likely some cohort of leveraged traders who will become forced sellers at some point. This awkward imbalance will compound the pressures on longer-term investors to evaluate stock ownership based on fundamental and valuation merits rather than as a function of exposure to some broader theme such as QE. Regardless of specific timing, astute investors will be well aware that stock prices based on fundamentals, in general, are substantially lower than current market prices today.

While it is fair to think of this past period of QE as an illusion, interest rates have not been the only things affected. With the Fed willing to put on such a show for interest rates, it is not unreasonable to expect similar illusions are being created with other economic and financial data. This isn’t so much a conspiracy theory as an observation of political reality: When economic numbers are not good and politicians want to get re-elected and corporate executives want to continue reaping massive pay packages, these measures become politicized. As they do, investors need to account for more noise and less reliable signals in their capital allocation decisions. A logical consequence is that cash may play a bigger role in allocations than it has in the past.

Finally, although this is an uncertain environment, it is equally so for everyone. That means those with better tools and processes to establish underlying reality, to clearly identify the elephant in the room, will be much better placed to avoid disasters and to exploit real opportunities as they emerge.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed