November 2018

Technology has touched our lives in so many ways, and especially so for investors. Not only has technology provided ever-better tools by which to research and monitor investments, but tech stocks have also provided outsized opportunities to grow portfolios. It's no wonder that so many investors develop a strong affinity for tech.

Just as glorious as tech can be on the way up, however, it can be absolutely crushing on the way down. Now that tech stocks have become such large positions in major US stock indexes as well as in many individual portfolios, it is especially important to consider what lies ahead. Does tech still have room to run or has it turned down? What should you do with tech?

For starters, recent earnings reports indicate that something has changed that deserves attention. Bellwethers such as Amazon, Alphabet and Apple all beat earnings estimates by a wide margin. All reported strong revenue growth. And yet all three stocks fell in the high single digits after they reported. At minimum, it has become clear that technology stocks no longer provide an uninterrupted ride up.

These are the kinds of earnings reports that can leave investors befuddled as to what is driving the stocks. Michael MacKenzie gave his take in the Financial Times late in October [here]: "The latest fright came from US technology giants Amazon and Alphabet after their revenue misses last week. Both are highly successful companies but the immediate market reaction to their results suggested how wary investors are of any sign that their growth trajectories might be flattening."

Flattening growth trajectories may not seem like such a big deal, but they do provide a peak into the often-tenuous association between perception and reality for technology. Indeed, this relationship has puzzled economists as much as investors. A famous example arose out of the environment of slowing productivity growth in the 1970s and 1980s [here] which happened despite the rapid development of information technology at the time. The seeming paradox prompted economist Robert Solow to quip [here], "You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics."

The computer age eventually did show up in the productivity statistics, but it took a protracted and circuitous route there. The technologist and futurist, Roy Amara, captured the essence of that route with a fairly simple statement [here]: "We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run." Although that assertion seems innocuous enough, it has powerful implications. Science writer Matt Ridley [here] went so far as to call it the "only one really clever thing" that stands out among "a great many foolish things that have been said about the future."

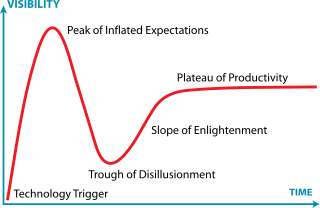

Gartner elaborated on the concept by describing what they called "the hype cycle" (shown below). The cycle is "characterized by the 'peak of inflated expectations' followed by the 'trough of disillusionment'." It shows how the effects of technology get overestimated in the short run because of inflated expectations and underestimated in the long run because of disillusionment.

Amara's law describes the dotcom boom and bust of the late 1990s and early 2000s to a tee. It all started with user-friendly web browsers and growing internet access that showed great promise. That promise lent itself to progressively greater expectations which led to progressively greater speculation. When things turned down in early 2000, however, it was a long way down with many companies such as the e-tailer Pets.com and the communications company Worldcom actually going under. When it was all said and done, the internet did prove to be a massively disruptive force, but not without a lot of busted stocks along the way.

How do expectations routinely become so inflated? Part of the answer is that we have a natural tendency to adhere to simple stories rather than do the hard work of analyzing situations. Time constraints often exacerbate this tendency. But part of the answer is also that many management teams are essentially tasked with the effort of inflating expectations. A recent Harvard Business Review article [here] (h/t Grants Interest Rate Observer, November 2, 2018) provides revealing insights from interviews with CFOs and senior investment banking analysts of leading technology companies.

For example, one of the key insights is that "Financial capital is assumed to be virtually unlimited." While this defies finance and economics theory and probably sounds ludicrous to most any industrial company executive, it passes as conventional wisdom for tech companies. For the last several years anyway, it has also largely proven to be true for both public tech-oriented companies like Netflix and Tesla as well as private companies like Uber and WeWork.

According to the findings, tech executives, "believe that they can always raise financial capital to meet their funding shortfall or use company stock or options to pay for acquisitions and employee wages." An important implication of this capital availability is, "The CEO’s principal aim therefore is not necessarily to judiciously allocate financial capital but to allocate precious scientific and human resources to the most promising projects ..."

Another key insight is, "Risk is now considered a feature, not a bug." Again, this defies academic theory and empirical evidence for most industrial company managers. Tech executives, however, prefer to, "chase risky projects that have lottery-like payoffs. An idea with uncertain prospects but with at least some conceivable chance of reaching a billion dollars in revenue is considered far more valuable than a project with net present value of few hundred million dollars but no chance of massive upside."

Finally, because technology stocks provide a significant valuation challenge, many tech CFOs view it as an excuse to abdicate responsibility for providing useful financial information. "[C]ompanies see little value in disclosing the details of their current and planned projects in their financial disclosures." Worse, "accounting is no longer considered a value-added function." One CFO went so far as to note "that the CPA certification is considered a disqualification for a top finance position [in their company]."

While some of this way of thinking seems to be endemic to the tech industry, there is also evidence that an environment of persistently low rates is a contributing factor. As the FT mentions [here], "When money is constantly cheap and available everything seems straightforward. Markets go up whatever happens, leaving investors free to tell any story they like about why. It is easy to believe that tech companies with profits in the low millions are worth many billions."

John Hussman also describes the impact of low rates [here]: "The heart of the matter, and the key to navigating this brave new world of extraordinary monetary and fiscal interventions, is to recognize that while 1) valuations still inform us about long-term and full-cycle market prospects, and; 2) market internals still inform us about the inclination of investors toward speculation or risk-aversion, the fact is that; 3) we can no longer rely on well-defined limits to speculation, as we could in previous market cycles across history."

In other words, low rates unleash natural limits to speculation and pave the way for inflated expectations to become even more so. This means that the hype cycle gets amplified, but it also means that the cycle gets extended. After all, for as long as executives do not care about "judiciously allocating capital", it takes longer for technology to sustainably find its place in the real economy. This may help explain why the profusion of technology the last several years has also coincided with declining productivity growth.

One important implication of Amara's law is that there are two distinctly different ways to make money in tech stocks. One is to identify promising technology ideas or stocks or platforms relatively early on and to ride the wave of ever-inflating expectations. This is a high risk but high reward proposition.

Another way is to apply a traditional value approach that seeks to buy securities at a low enough price relative to intrinsic value to ensure a margin of safety. This can be done when disillusionment with the technology or the stock is so great as to overshoot realistic expectations on the downside.

Applying value investing to tech stocks comes with its own hazards, however. For one, several factors can obscure sustainable levels of demand for new technologies. Most technologies are ultimately also affected by cyclical forces, incentives to inflate expectations can promote unsustainable activity such as vendor financing, and debt can be used to boost revenue growth through acquisitions.

Further, once a tech stock turns decidedly down, the corporate culture can change substantially. The company can lose its cachet with its most valuable resource — its employees. Some may become disillusioned and even embarrassed to be associated with the company. When the stock stops going up, the wealth creation machine of employee stock options also turns off. Those who have already made their fortunes no longer have a good reason to hang around and often set off on their own. It can be a long way down to the bottom.

As a result, many investors opt for riding the wave of ever-inflating expectations. The key to succeeding with this approach is to identify, at least approximately, the inflection point between peak inflated expectations and the transition to disillusionment.

Rusty Guinn from Second Foundation Partners provides an excellent case study of this process with the example of Tesla Motors [here]. From late 2016 through May 2017 the narrative surrounding Tesla was all about growth and other issues were perceived as being in service to that goal. Guinn captures the essence of the narrative: "We need capital, but we need it to launch our exciting new product, to grow our factory production, to expand into exciting Semi and Solar brands." In this narrative, "there were threats, but always on the periphery."

Guinn also shows how the narrative evolved, however, by describing a phase that he calls "Transitioning Tesla". Guinn notes how the stories about Tesla started changing in the summer of 2017: "But gone was the center of gravity around management guidance and growth capital. In its place, the cluster of topics permeating most stories about Tesla was now about vehicle deliveries."

This meant the narrative shifted to something like, "The Model 3 launch is exciting AND the performance of these cars is amazing, BUT Tesla is having delivery problems AND can they actually make them AND what does Wall Street think about all this?" As Guinn describes, "The narrative was still positive, but it was no longer stable." More importantly, he warns, "This is what it looks like when the narrative breaks."

The third phase of Tesla's narrative, "Broken Tesla", started around August 2017 and has continued through to the present. Guinn describes, "The growing concern about production and vehicle deliveries entered the nucleus of the narrative about Tesla Motors in late summer 2017 and propagated. The stories about production shortfalls now began to mention canceled reservations. The efforts to increase production also resulted in some quality control issues and employee complaints, all of which started to make their way into those same articles."

Finally, Guinn concludes, "Once that happened, a new narrative formed: Tesla is a visionary company, sure, but one that doesn’t seem to have any idea how to (1) make cars, (2) sell cars or (3) run a real company that can make money doing either." Once this happens, there is very little to inhibit the downward path of disillusionment.

Taken together, these analyses can be used by investors and advisors alike to help make difficult decisions about tech positions. Several parts of the market depend on the fragile foundations of growth narratives including many of the largest tech companies, over one-third of Russell 2000 index constituents that don't make money, and some of the most over-hyped technologies such as artificial intelligence and cryptocurrencies.

One common mistake that should be avoided is to react to changing conditions by modifying the investment thesis. For example, a stock that has been owned for its growth potential starts slowing down. Rather than recognizing the evidence as potentially indicative of a critical inflection point, investors often react by rationalizing in order to avoid selling. Growth is still good. The technology is disruptive. It's a great company. All these things may be true, but it won't matter. Growth is about narrative and not numbers. If the narrative is broken and you don't sell, you can lose a lot of money. Don't get distracted.

In addition, it is important to recognize that any company-specific considerations will also be exacerbated by an elemental change in the overall investment landscape. As the FT also noted, "But this month [October] can be recognised as the point at which the market shifts from being driven by liquidity to being driven by fundamentals." This turning point has significant implications for the hype cycle: "Turn off the liquidity taps at the world’s central banks and so does the ability of the market to believe seven impossible things before breakfast."

Yet another important challenge in dealing with tech stocks that have appreciated substantially is dealing with the tax consequences. Huge gains can mean huge tax bills. In the effort to avoid a potentially complicated and painful tax situation, it is all-too-easy to forego the sale of stocks that have run the course of inflated expectations.

As Eric Cinnamond highlights [here], this is just as big of a problem for fiduciaries as for individuals: "The recent market decline is putting a growing number of portfolio managers in a difficult situation. The further the market falls, the greater the pressure on managers to avoid sending clients a tax bill." Don't let tax considerations supersede investment decisions.

So how do the original examples of Amazon, Alphabet and Apple fit into this? What, if anything, should investors infer from their quarterly earnings and the subsequent market reactions?

There are good reasons to be cautious. For one, all the above considerations apply. Further, growth has been an important part of the narrative of each of these companies and any transition to lower growth does fundamentally affect the investment thesis. In addition, successful companies bear the burden of ever-increasing hurdles to growth as John Hussman describes [here]: "But as companies become dominant players in mature sectors, their growth slows enormously."

"Specifically," he elaborates, "growth rates are always a declining function of market penetration." Finally, he warns, "Investors should, but rarely do, anticipate the enormous growth deceleration that occurs once tiny companies in emerging industries become behemoths in mature industries." For the big tech stocks, wobbles from the earnings reports look like important warning signs.

In sum, tech stocks create unique opportunities and risks for investors. Due to the prominent role of inflated expectations in so many technology investments, however, tech also poses special challenges for long term investors. Whether exposure exists in the form of individual stocks or by way of major indexes, it is important to know that many technology stocks are run more like lottery tickets than as a sustainable streams of cash flows. Risk may be perceived as a feature by some tech CFOs, but it is a bug for long term investment portfolios.

Finally, tech presents such an interesting analytical challenge because the hype cycle can cause perceptions to deviate substantially from the reality of development, adoption and diffusion. Ridley describes a useful general approach: "The only sensible course is to be wary of the initial hype but wary too of the later scepticism." Long term investors won't mind a winding road but they need to make sure it can get them to where they are going.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed